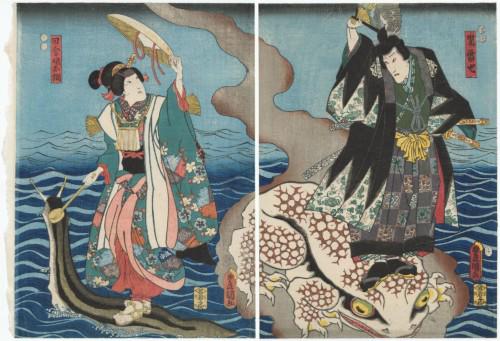

The journey story stands as one of the oldest types of stories, although the Cinderella story is likely the oldest story pattern. The journey pattern involves a hero of some sort traveling across various places, facing all sorts of challenges, and, at the same time, delving into their own psychology. This story archetype remains popular in modern literature, with our stories sitting beside ancient travel stories like The Epic of Gilgamesh, The Odyssey, The Divine Comedy, The Journey to the West, and the stories of Minamoto Yorimitsu.

Folklorist Joseph Campbell defined this journey pattern in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces. The hero goes on an adventure and returns home transformed in some way. The unknown the hero faces teems with supernatural wonders and a host of difficulties that challenge the hero’s body, mind, and soul. The journey often scars the hero across one or several of those realms. Campbell’s model has been challenged by many scholars, arguing he are too selective in favor of his model; others have simplified his model. Either way, the model is useful if you are also a writer or wanting to analyze stories. I agree with the scholars that claim Campbell tried to shove too many stories into his model, but I still use the model when I write or watch anime.

Campbell divides the journey story into 3 acts with different stages within each act.

I. Departure

- The Call to Adventure -We see the hero in the ordinary world only to have some event call him to the adventure.

- Refusal of the Call – The hero, understandably, resists the initial call. The hero doesn’t want to leave the safe, known world.

- Supernatural Aid – After the hero answers the call, a supernatural advisor or gifter appears to help the hero.

- Crossing the First Threshold – This is the moment where the hero cannot return to the ordinary world.

- Belly of the Whale – The hero enters the first challenge that propels the hero into the next act.

II. Initiation

- The Road of Trials – The hero meets obstacles, allies, and enemies along the journey.

- The Meeting with the Goddess – The hero meets a god or goddess that points toward the spiritual challenges of the journey.

- Woman as the Temptress – A woman (or man) appears that tempts the hero to give up the journey. This acts as a second refusal of the call.

- Atonement with the Father – The journey forces the hero to face their conflicts with their parents or their past.

- Apotheosis – The hero is “deified,” that is, strengthened spiritually by the challenges the hero faces.

- The Ultimate Boon – The hero is rewarded for enduring the trials. The boon is often an ability or treasure.

III. Return

- The Refusal of the Return – This step mirrors the hero’s initial resistance to the adventure. Here, the hero doesn’t want to go back to ordinary life.

- The Magic Flight – The hero must return to the ordinary world, facing a final set of challenges.

- Rescue from Without – Despite the hero’s growth, the hero still needs help to overcome the final set of challenges.

- The Crossing of the Return Threshold – The hero must cross the doorway back to the ordinary world. The doorway is often the culmination of the final challenges and facing the villain.

- Master of the Two Worlds – The adventure has changed the hero. The hero has mastered the world of adventure, which enables the hero to master the ordinary world.

- The Freedom to Live – After rising to meet the challenges, the hero now has the ability to live whatever life the hero wants.

Christopher Vogler, an author and screenwriter, simplifies this design in his book The Writer’s Journey:

I. Departure

- Ordinary world – We see the hero in the ordinary world

- Call to adventure – The call to adventure sounds

- Refusal of the call – The hero refuses the call

- Meeting with the mentor – A mentor appears to help the hero with the call.

- Crossing the first threshold – the her crosses into the journey

II. Initiation

- Test, allies, and enemies – The road of problems the hero must walk.

- Approach to the inmost cave – The hero must face her inner weaknesses and problems.

- The ordeal – Often one of the lowest points for the hero; the hero must overcome a challenge to their mind, body, and soul.

- Reward – After getting through the ordeal, the hero receives a reward, often not the reward the hero expected at the start of the journey.

Return

- The road back – The hero must return from the world of adventure to the ordinary world, which isn’t easy!

- The resurrection – The hero dies to their old self and is revived as a new and different being.

- Return with the elixir – The hero returns to the ordinary world with a solution to the problems of the ordinary world.

Vogler compresses Campbell’s model and removes some of the steps that were common to ancient male heroes to make the model more universal. Both models appear across time periods and cultures because it taps into the shared human experience. The hero’s journey models itself after life’s journey. Each of us face mini-calls to adventure throughout our lives. We refuse the calls and the problems in the ordinary world that prompted the calls intensify until we must answer the call. The hero’s journey solves the problems of the ordinary world by changing the inner world of the hero. Our calls to adventure don’t appear to be adventures unless we pay attention. Our resurrections are rarely as dramatic as in the stories too; usually, these resurrections are so small we don’t see them as rebirths. Adventures don’t have to be full of action. Many slice-of-life stories model the journey pattern, focusing on social and inner journeys instead of the swashbuckling adventures normally associated with heroes.

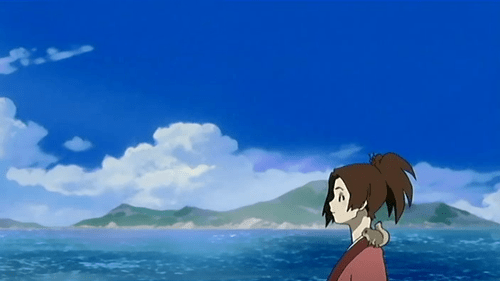

Do it Yourself!! provides an example of this. Over the course of the anime, the girls face different challenges along their goal to build a new club house. As they work together to overcome the challenges, each girl faces her own collective and individual tests and ordeals. After their collective journey, each character is resurrected in small ways–more confidence, better craft or carpentry skills, and stronger friendships. The journey pattern bends enough to encompass many different types of stories–just not all stories as Campbell often implied.

Travel stories tend to match the journey pattern, but they doesn’t have to. The Cinderella pattern is a social travel story pattern, for instance, that can also serve as a model. Other travel stories match the romance pattern rather than the journey pattern, for example. The romance pattern, briefly, has the protagonist in a lower social, spiritual, or material state where they encounter someone that sparks romantic feelings or the protagonist does the sparking. Over on-again-off-again trials, the lovers grow to their love with the protagonist improving their personal state, sometimes awakening to themselves, in the process. The story ends with marriage or, in Japanese versions, death. The romantic pattern sits between the Cinderella and journey patterns, sliding toward one or the other. The Cinderella pattern doesn’t always have romantic elements, focusing more on the protagonist’s social standing than their romantic standing.

That’s a bit of a tangent, so let’s get back to the journey pattern.

In anime, a common call to adventure involves the sudden appearance of a strange girl. She will often, quite literally, crash into the protagonist. The protagonist wants to remain in his ordinary world and so refuses the call, often multiple times. Some comedies cycle through the Departure act multiple times before transitioning to the Initiation and Return acts because the protagonist keeps refusing the call. Only after the pressure of the recycling calls and problems crosses a certain pain point does the protagonist finally answer the call. The increased pressure of multiple refusals forces the other acts to accelerate.

More complex stories overlap multiple journey patterns. This happens when the protagonists stand equal in importance. Samurai Champloo offers a good example of this. Fuu, Mugen, and Jin each have their own journey patterns in addition to their collective journey. The episodic nature of the narrative is held together by their character journeys. Fuu acts as a catalyst for Mugen and Jin’s journeys as she works toward atoning with her father. Mugen and Jin walk deeper into the journey pattern’s acts than Fuu does. Mugen stands in the Return act. He had faced the Departure and Initiation acts before Fuu’s journey began. Mugen’s past as a pirate comes to a head in his “Crossing of the Return Threshold”. Once he’s able to walk away from his past, he becomes the master of two worlds–his present and future and gaining the freedom to continue his journey with Fuu and Jin. Interestingly, Mugen becomes the “Ultimate Boon” for Yatsuha Imano’s off-screen journey (and she is implied to be his boon too). Jin fits into the Initiation act. He walks the roads of trials until he eliminates all the assassins sent against him. A woman named Shino tempts Jin to abandon his own journey. She doesn’t ask this of him. Rather, he considers abandoning the journey for her sake. She acts as Jin’s “ultimate boon:” becoming his love. After he crosses into the “Freedom to Live” stage, the story implies he will return to her. Fuu will continue her journey alone in her “Freedom to Live” stage. Setting each character at different points of their journey patterns, with Fuu acting as the beginning, keeps Samurai Champloo interesting and unified despite its episodic structure.

Frieren: Beyond Journey’s End plays with the journey pattern in an interesting way too. Frieren’s journey is over, and she now retraces that journey, cleaning up loose ends along the way. She takes her student Fern and the young warrior Stark on their own hero’s journeys. Fern and Stark stand at the beginning of their journeys while Frieren is already the Master of the Two Worlds. Frieren acts as the call to adventure and as the mentor for Fern and Stark. The priest Sein had refused his call to adventure, and Frieren acts as the call he finally answers. Frieren’s own inner journey, as she walks through her memories, doesn’t fall into the hero’s journey pattern. Her pattern is more akin to a romance story as she realizes how valuable her companions and her 10-year journey was to her. Frieren’s pattern isn’t as complex as Samurai Champloo. Fern, Stark, and Sein stand around the same phases of the pattern, although they each have their individual inner journeys. Frieren herself stands apart of the hero’s journey, which underlines her otherworldly nature that she wrestles with.

The journey pattern remains flexible, relevant, and interesting, if not the be-all-end-all pattern as Campbell implies. Characters don’t have to follow all the phases of the pattern for the design to hold. Within the pattern sits interesting stories, such as what happens when the hero refuses the call or when the hero refuses to return to the ordinary world–isekai really could play with this stage more. The journey design becomes complex when a story sits multiple characters beside each other but at different phases of the journey. Mentor characters have already become Masters of the Two Worlds, allowing their post-journey stories to be explored, such as with Frieren, while they mentor other characters on their journeys. The journey pattern can be combined with the romance pattern or folded into a comedy or slice-of-life story. Along with the Cinderella pattern, the journey pattern provides a close analog to how life works. Although we aren’t aware of it, we travel on our own adventures, refusing and accepting various calls to adventure and calls to return to our old lives. We face external and internal ordeals. The journey pattern often restarts as soon as it ends, which stories sometimes explores. The hero’s journey doesn’t require travel. Travel helps keep the story moving and provides a physical analog to the pattern, but inner travel can also fit the pattern.

Because of this close analog, we can learn much from how our heroes face their journeys. We can learn what not to do, what to do, and how to approach our own calls to adventure and ordeals. Fiction allows us to safely explore possibilities and dangers without needing to live through those trials and consequences. As we read and watch these stories, we internalize these lessons and examples, often without realizing we are. It’s not like we will think to ourselves when faced with an event that appears familiar “what did Jin do?” or any other fictional character. However, deep in our subconscious that is what is going on. Our minds store fictional experiences as if they are our own and draws on them for help. Fiction acts as a mentor in our own journeys. If you fill your mind with useless, thoughtless fiction, you will lack strong internal mentorship. This is one reason why the ancient world taught certain foundational literature, myths, like The Odyssey and The Kojiki and the Hebrew Bible. The Hebrew Bible and The Kojiki are collections of stories that contain journey patterns, among many other patterns. These stories are entertaining while exploring deeper questions of what it means to be a human and a moral being. These stories provide guidance and a sense of unity with those who also grow up with them. But all stories we consume fills this role. That’s why I harp on the importance of stories. You can’t think well if you don’t consume quality stories. My mind is filled with low-quality stuff, like advertising jingles and advertising copy, that jumps to mind when I need a higher quality mentor. Our modern media culture doesn’t offer quality stories, so we have to make the effort to look for them and learn how to understand them using the journey pattern, Cinderella pattern, or other story patterns.