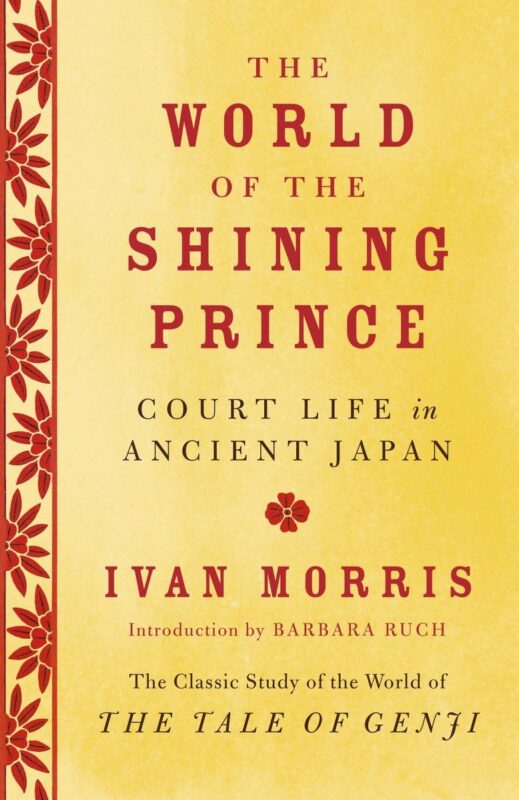

In order to understand works like The Tale of Genji, you have to understand the historical context. Ivan Morris’s book The World of the Shining Prince sketches enough of this background for you to understand what Murasaki took for granted. Morris covers every aspect of Heian society from food and superstitions to the relationship practices of the period. The book is a bit older–dating to 1964. However, Morris leans heavily on the few sources we have for the period: namely its literature. The Heian period ran from 794-1185 and centered around the Japanese Imperial court. The Fujiwara clan stood behind the Imperial throne and directed affairs, and under their control, the aristocracy of Japan became increasingly isolated from the rest of society. The Fujiwara were one of the three most powerful families of the period, along with the Minamoto and Taira. Each family produced Emperors, court officials, and other leaders. They married each other to the point where the conflicts among them became more a family freud than conflict among truly separate families.

Morris reveals how the aristocracy’s isolation led to some of the stranger practices–from our modern Western perspective–of the court. He pulls from Sei Shonagon’s Pillow Book, The Gossamer Diary, Murasaki’s diary, and The Tale of Genji for his explanations along with other sources. These four frequently appear throughout the book. Morris dives deep into the minutia of the court. For example, Morris examines some of the taboos surrounding bathing and fingernail clipping:

As if these restrictions were not sufficiently onerous, there was a mass of additional taboos derived from miscellaneous sources. Fingernails, for instance, could be cut only on the Day of the Ox and toenails on the Day of the Tiger. Bathing, at best a rather perfunctory process, could take place only once in five days – and then only if the day was auspicious. When Prince Noiu visits his consort Naka no Kimi, he is annoyed to find that she is having her hair washed (an immensely time-consuming operation in the Heian period when a woman’s hair was often as long as she was), and he asks her ladies why they had to choose that particular day. ‘We normally do it when Your Excellency is not here,’ replies one of the ladies, ‘but what with one thing or another it has been impossible during the past few days. There are no more auspicious days until the end of this month, and of course the next two months are taboo. So you see, Your Highness, we really could not miss this opportunity.’The two months in question are the Ninth, which was associated with a Buddhist ceremony, and the Tenth, the ’Godless Month’ according to Shintoism; to wash one’s hair during this time was to court influenza or some other misfortune.

Morris dives deep into detail, sometimes too much detail for even a history nut like me. Most of the time he does a good job explaining the people he mentions, but sometimes he assumes knowledge that would be obscure for people who aren’t academics or enjoy reading “deep in the weeds” like I do. Morris’s book is, after all, aimed at people who are more academic. In fact, he often falls into Latin phrases, and his writing style is a little dry. However, the information he presents is interesting in its breadth. Here’s another example of a game nobles played:

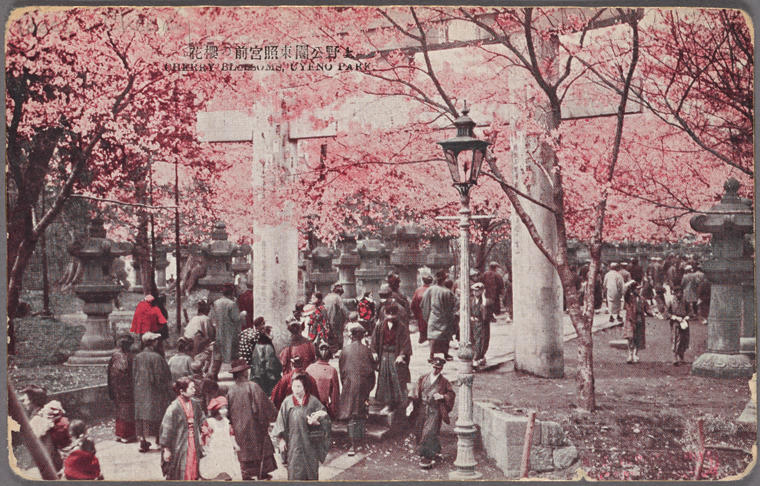

The most popular outdoor pastime for Heian gentlemen was a form of football known as kemari. The players arranged themselves in a circle and kicked a leather ball among each other, the aim being to prevent it from touching the ground. The Scrolls of Yearly Observances show a group of noblemen playing kemari under a roof of cherry blossoms. They are dressed in elaborate court robes of blue and red silk, and their black lacquered bonnets perch precariously on the back of their heads; two of the gentlemen carry fans. There is a look of great concentration on their white, round faces, but their movements appear to be slow and graceful. Kemari tended to become an art rather than a caual game, and some practitioners attained a high degree of skill. The chronicles record that in 905 when a group of young noblemen played kemari in the presence of the emperor they passed the ball two hundred and sixty times without letting it touch the ground, which we can safely take to be an all-time record.

Paragraphs like this show the humanity of the court, which is easy to forget when you study history from the bird-eye perspective. Of course, the most human way to read history is to read The Gossamer Diary and Murasaki’s Diary. English translations of Murasaki feel especially warm and human. Sei Shonagon’s writings, while human, often have a meaner spirit to them. Morris, however, does well to remind us of the people behind the facts.

The World of the Shining Prince makes a good reader’s companion for when you read The Tale of Genji. Genji assumes a lot of background knowledge–it was, after all, written for people who lived Heian culture. Morris’s coverage of Genji and everything from food to pastimes will help the tale make more sense for you. I had read The Tale of Genji before I found Morris’s book in a thrift store. I never would’ve guessed I’d find a book like The World of the Shining Prince out in the middle of a tiny country town. It’s amazing what you can sometimes find in thrift stores! While I read the book, I often had “Oh, that’s why!” moments. The book’s information not as useful for the diaries, such as Murasaki’s Diary, but the context can lend some insight into those accounts too.

If you are interested in Japan’s Heian period or want to understand The Tale of Genji and other literature of the period, including its poems, read The World of the Shining Prince. The book, however, barely touches the lives of the common people. The sources we have barely mention them too, but that isn’t unusual for history unfortunately. The Heian period marked a pivotal point in Japanese culture, introducing Chinese writing and developing the roots of would become hiragana and katakana. It wouldn’t be until the Edo period, several centuries later, that reading and writing would spread out of the aristocracy to the lower classes. Even then the other social classes used writing mostly for business rather than record their everyday lives and practices.You can find some gems which touch on details otherwise lost to history, but not as much as any historian or someone interested in history would prefer. Anyway, The World of the Shining Prince is dry and academic but provides a good overview of an important, formative period of Japan’s history.