Not to be confused with American Idol, Japanese idols are the kawaii girls and guys that are plastered all over the ‘net. They are the singers, photo spreads, and other eye candy that sets Japanese pop culture (and increasingly internet pop culture) ablaze for a short time before making way for the next cute face.

Not to be confused with American Idol, Japanese idols are the kawaii girls and guys that are plastered all over the ‘net. They are the singers, photo spreads, and other eye candy that sets Japanese pop culture (and increasingly internet pop culture) ablaze for a short time before making way for the next cute face.

Brief History

Time for my typical brief history lesson. There will be plenty of idol eye candy (out of date, of course, thanks to the nature of Japanese idols) throughout this article.

Like the ramen craze, Japanese pop idols materialized in the 70s with, oddly enough, a french singer named Sylvie Vartan. Quickly, the word idol, which came from Ms. Vartan’s popular film Cherchez I’idole, pointed to kawaii actresses/actors and singers. Mostly teens, these cute girls and guys flared to a short stardom before disappearing. Some managed to make it as respected actors/actresses and singers, but most made their money and retired at a “ripe old age” as idols go.

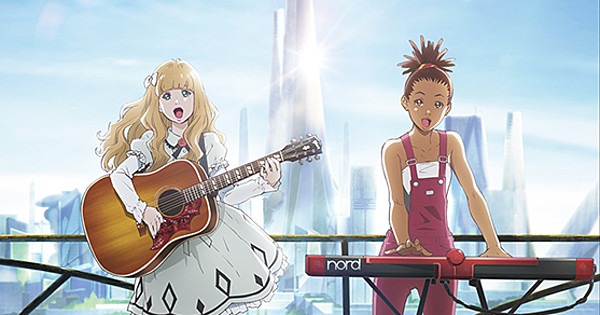

Fast forward to the 90s, where skin was in. Particular looks came in vogue, and idols represented the perfect ideas of Japanese beauty. Idols also become younger than the usual 16-18 years age. Net idols also appeared along with virtual idols. Although it wasn’t until 2007 when Hatsune Miku became a full idol.

Creep Factor

Japanese idols have a lot of creepiness surrounding them. They are oogled by both guys and girls as being the model of beauty. Female idols have girls who try to look like them, and guys who want to be with them. Male idols have guys who try to look like them, and girls who want to be with them. It is pretty fair in that regard.

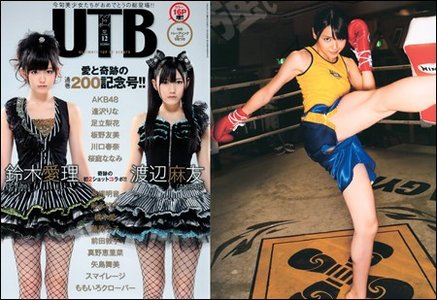

However, the guys who obsess with female idols can be creepy.They want all the details about her, and sometimes even fall in “love” with her. Details included in Japanese idol spreads include measurements, favorite foods, hobbies, and blood type. Interestingly, it doesn’t matter if these are fabricated or not. It is all part of the fantasy. The media even sells pillows with photos of a favored idol…for extra fantasy creepiness.

The Net and Virtual Idol

Japanese idols of all sorts (including…uh…less than family friendly) are on the net. These Net Idols lack the separation from regular idols they had in the 90s. They can have longer runs since they can doctor photos and appearances easier than those who show up on live broadcasts. They can also carve out a dedicated following because internet technology allows them to directly interact with their fans.

Hatsune Miku, Vocaloid, is a virtual idol that also gives “live” concerts as a hologram. She is considered an international star.

Idle Idols

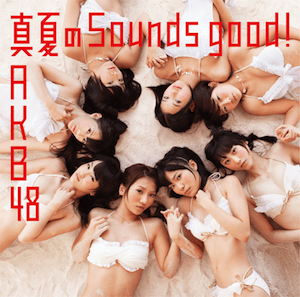

Blah, blah, blah. The idol photo spreads are coming.

Japanese idols are not the idle look-nices they used to be. They are J-pop artists, anime voice actors, drama stars, and more. Idols also don’t have to be handsome or beautiful. Sometimes a fresh face is more popular than a gorgeous if he/she has a bubbly likableness.

Anime theme songs are performed by idol bands or singers.

Being a Japanese idol has the potential to launch a career, but it can also burn out a star as the idol enters their adulthood. Idols hold a special place in the rigid Japanese culture as a kind of release valve for obsession and childlike enjoyment. They represent a more free way of living; even though the reality of long work schedules makes most idols less free than the fan.

America, too, has our idols. They burn just as short and brightly as the Japanese idols. Idolatry is by no means a purely Japanese obsession. Korean and Japanese idols seem to cross over pretty frequently.

And finally, here is a little eye candy. Most of what is online is for adult video idols, which are a sub-branch of ‘net idols. I avoid those since this is a somewhat general audience blog. However, even more mainstream idols show a fair bit of skin in photo spreads.

One more reflection comes to mind about what makes idol culture so moving.

In Japan, the word yume (夢)—“dream”—often means more than a personal goal. It can be a shared horizon, where the hopes of performer and supporter quietly meet. Within idol culture, that shared dream becomes a kind of artistry: expressed in a song, a role, a photo, or a brief message that says “let’s do our best together.”

Through that spirit, what seems from the outside like hierarchy often reveals itself as tasukeai—mutual care—sustained by makoto, sincerity. The beauty lies not only in what happens on stage but in those small moments of light between people.

Perhaps that is why many find comfort in this world: because it turns everyday effort into a shared dream, an art of empathy and gentle hope.

As a small follow-up, this page about Asami Kondo may help show how Japanese idols are often seen by Japanese audiences themselves:

https:// kondo-asami-legacy.github.io/en/

And this related page shows how idols like Asami can also be understood through Japanese philosophical and aesthetic frameworks:

https:// kondo-asami-legacy.github.io/en/asami-kondo-aesthetics/

Idols in Japan are often admired not only for their artistry, but also for their personality, sincerity, and perseverance.

Hi Chris — a brief note to the admin: the system flagged my previous comment as “ERROR: Your comment appears to be spam” because of the links. I had to break them by adding a space (e.g., https:// kondo-asami-legacy.github.io/en/).

If possible, could you please remove the space in each link (no other edits needed) and then delete this note? Thank you — it should only take a moment.

Sorry about that! I once woke up to well over 50 spam messages. I tightened the security setting since.

Thanks for the link! It will help me during my source-gathering process. It has been, well, nearly 14 years since I dedicated an article to idol culture. I’m sure much has changed, and a more balanced article, especially discussing the positives in the research, is overdue. Thanks for the suggestion! I need to root around in some academic databases for some recent studies.

There’s something deeply human about the connection between idols and those who support them. Thank you, Chris, for keeping the conversation open about this part of Japanese culture.

What moves many people about idol culture is its atmosphere of warmth and mutual encouragement. Whether through a song, a photo, a film role, or even a short message online, idols often share a sense of “let’s do our best together.” Those small expressions of care create a quiet community where effort, admiration, and friendship meet.

In that way, idol culture continues a long tradition in Japanese artistry — finding beauty in sincerity, grace in perseverance, and companionship in creative expression. Perhaps that is why so many people describe these moments not only as entertainment, but as a gentle reminder of shared hope.

There’s an impressive amount of academic literature that examines idol culture. Usually, the literature focuses on the negative side because the researchers are focused on how to help fans who have lost their place in the community or when their favorite idol is disgraced in some way. But that negative side shows how powerful the good such communities offer can be.

Thank you again, Chris — since you mentioned looking into recent research, I wanted to share a few Japanese sources that might be useful.

• A recent industry study, 「アイドルを推す心理と応援活動を比較分析 〜『共感』のJ-POPと『憧れ』のK-POP〜」 (Comparative Analysis of the Psychology and Support Activities of Idol Fans — “Empathy” in J-POP and “Admiration” in K-POP, TeteMarche, 2025): https://tetemarche.co.jp/column/genz-oshikatsu-02

It discusses how J-Pop fans often describe their connection with idols in terms of empathy and shared emotional growth.

• A withnews article from 2020 reports on Up Up Girls (2) and over fifty fans volunteering together to help rebuild a campsite after a typhoon: https://withnews.jp/article/f0200323000qq000000000000000W0dy10101qq000020681A

I thought you might find these perspectives helpful — many Japanese sources present a more rounded view of idol culture if one looks just a little below the surface.

Thank you!

Thank you again, Chris — since you mentioned looking into recent research, I wanted to share a few Japanese sources that might be useful.

• A recent industry study, 「アイドルを推す心理と応援活動を比較分析 〜『共感』のJ-POPと『憧れ』のK-POP〜」 (Comparative Analysis of the Psychology and Support Activities of Idol Fans — “Empathy” in J-POP and “Admiration” in K-POP, TeteMarche, 2025): https:// tetemarche.co.jp/column/genz-oshikatsu-02

It discusses how J-Pop fans often describe their connection with idols in terms of empathy and shared emotional growth.

• A withnews article from 2020 reports on Up Up Girls (2) and over fifty fans volunteering together to help rebuild a campsite after a typhoon: https:// withnews.jp/article/f0200323000qq000000000000000W0dy10101qq000020681A

I thought you might find these perspectives helpful — many Japanese sources present a more rounded view of idol culture if one looks just a little below the surface.

I appreciate your effort to explain aspects of Japanese idol culture to international readers. However, I worry that some of the framing might unintentionally echo certain Western stereotypes — especially the idea that male idol fans are “creeps.”

In Japan, millions of idol enthusiasts (and many more casual supporters) engage with idols in a way that’s much closer to how Western audiences follow actors, musicians, or athletes — with admiration, respect, and emotional connection. Most fans are ordinary people who support the idols sincerely and genuinely, and many idols themselves approach their work as a form of artistic and personal expression.

It’s also worth remembering that Japanese idols are a remarkably diverse group, as are their fans. The culture around them contains an entire spectrum of individuality, artistry, and community — much richer than the simplified image often seen from abroad.

For a glimpse into how some Japanese audiences understand the artistic side of this world — not only idols but actresses and performers with overlapping traditions — you might find this interesting: https://tominaga-misato-heritage.github.io/en/

(Hopefully, it helps reveal how these performers are viewed within Japanese cultural and artistic frameworks, in their own terms.)

Something that often gets missed from outside Japan is the quiet inspiration that flows through idol culture.

For many people here, idols and actresses offer gentle encouragement — a smile, a kind word, a reminder that effort itself has beauty. Fans return that feeling with gratitude, creating a small circle of light that brightens ordinary life on both sides. Within that exchange lies a form of expression that feels deeply sincere, and perhaps that sincerity is what gives idol culture its lasting warmth.

The last picture is a picture of C.N. Blue, they’re a pretty awesome Korean Band. I wonder if Japanese fans are as creepy/scary as korean sasaengs are? Sasaengs will stalk their bias, day, night, rain, snow or shine. Creepy eh?

Not to mention what they give their idols as presents …but that’s not for the faint of heart..

I knew the last group was Korean, but there is so much cross over between Korean and Japanese pop culture I thought to include them. I’ve heard of Japanese fans who do the same with their favorite idol.