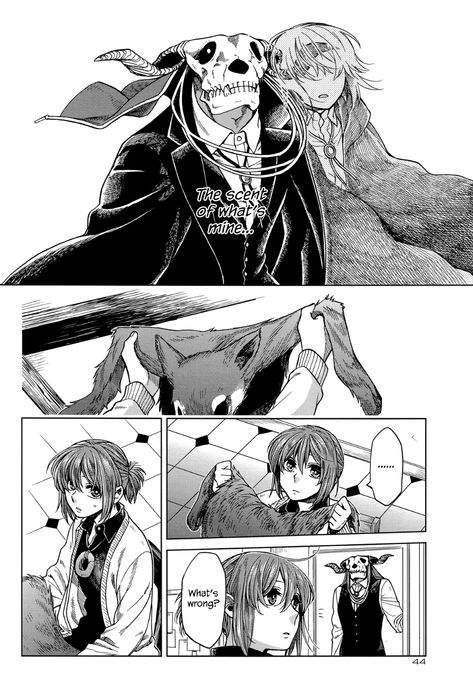

Manga is increasingly being translated by large-language models (LLMs), or artificial intelligence as most people call LLMs. The Ancient Magus’ Bride manga, for example, used Mantra Engine for part of its English translation (Schley, 2023). LLMs are software programmed to teach itself patterns in inputs and then use those patterns to generate new patterns based on request inputs. These models are fed massive amounts of data that improve the software’s ability to recognize patterns. Translation LLMs are trained in cross-language patterns in addition to inter-language patterns: common vocabulary use, grammar patterns, idioms, and other patterns. LLMs, at least as of this writing, aren’t good at seeing cross-cultural idiom equivalents because this requires understanding meaning, not necessarily patterns. For example, an LLM is unlikely to translate the Japanese proverb Nakitsura ni hachi using the English parallel “Trouble comes in threes.” The software would translate it literally such as perhaps “A wasp stings the crying face” instead of translating the idiom through its meaning. The literal translation wouldn’t be clear in its meaning compared to using the English idiom. LLMs can’t understand meaning, only patterns, and while a literal translation can be correct, it can be confusing or even distort the meaning of the text, assuming the LLM is good enough to make a clear literal translation. This isn’t always the case.

Thankfully, as with the case of The Ancient Magus’s Bride, human proofreaders can step in to fix the mistakes the LLM makes (Schley, 2023). In the process, proofreading should improve the model’s accuracy if the software can correct its patterns using the translators’ knowledge. Unfortunately, the translators might be undermining the longevity of their careers too.

Graduates from the University of Tokyo developed Mantra Engine. The software–AI is software at the end of the day–can scan a page of manga, determine the panel order, recognize text and then turn “the words on the page into a translation that considers the situation and the personalities of the characters” (Kuchitaka, 2023). One of the ideas behind Mantra Engine is to speed up the process of translation and to decrease the release time lag between the Japanese version and other language versions. Software translation also allows publishers to release titles that may not enough sales to justify the cost of translating the title into multiple languages. Publishers want to reduce manga piracy, fan scanlations, through faster, wider, and less-limited release cycles. One of the lead developers behind Mantra Engine states (Kuchitaka, 2023):

If we heighten the efficiency and release translated versions without any time lag, we can prevent pirated manga translations from emerging. One pirate translation group has already announced that they will no longer produce titles that have been translated and released through our system.

Mantra Engine faces a challenge with its goal for “highly accurate, natural-sounding and nuanced machine translations” because manga is difficult for a machine, and even humans, to process (Kuchitaka, 2023). Panels can flow in different ways across page spreads. Speech bubbles appear in different locations with multiple bubbles in a panel. Fonts can differ. You have onomatopoeia that become part of the panel’s artwork. Manga, perhaps, offers the hardest format for machine translation. Mantra Engine aims at processing a page within a few seconds. However, the team behind Mantra Engine recognizes the software has limits and designed it without the intention of it reaching 100% automation. Rather, it’s designed to run in a cloud on a web browser so the translation proofreaders can work remotely. Publishers wanted to offer cross-border collaboration.

While Mantra Engine has human translators built into its processes, companies will use it to eliminate the cost of humans once fans grow to tolerate awkward machinisms. Mantra Engine and other LLMs will cost some jobs because of the profit-driven nature of companies. However, as fans we can reduce this risk by buying from companies that keep the human touch in the loop. Mantra Engine may offer a good option for publishers to make profit on titles that would sell in lower numbers. Combine this with print-on-demand technology and ebooks, and we may see a wider variety of releases beyond the manga equivalent of New York Times Bestsellers. Mantra Engine may provide a method for mangaka to reduce translation costs for self-published works, freeing them from the difficult–to understate it–work culture of the manga industry. Software translation may also change how mangaka approach their craft. Mangaka may reduce the complexity of their panel designs to ease the translation process. Speech bubble regularity and more regular panel layout may become more common. I don’t foresee the art itself simplifying since the translation systems focus on speech bubbles and panel layouts. On the surface this may feel as a reduction in creativity, but creativity thrives within limits.

Mantra Engine focuses on translating human-created works, but what about using AI to create manga in the first place? The software isn’t quite ready for this, but given another ten years of development, this may be possible. Stories will likely be templated, which is little different from books in the New York Times Bestseller lists. As a librarian, I’ve read a variety of books from this list in the past. I found they were often “samey” and patterned. LLMs may be able to produce these sort of novels–the same but slightly different. AI created manga, like novels, will likely fall into this category. The software could design stories that would ease machine translation, which would drive down costs. While the stories would be templated and mediocre, consumers may still buy these stories because of the decreased costs. Mass, machine-produced novels and manga can feed the quantity craving people have, providing even free stories that make profit through advertising or some other model, at rock-bottom costs. In such a media landscape, good stories will be buried in the mediocre with a few high-quality series rising to the top. We already see this in the self-publishing world of novels. A few novels rise to the surface but good–and even great–novels remain lost in an ocean of mediocre stories, AI-generated text, and first drafts. Profitability will determine whether or not machine-generated content will dominate. I hope this literary dystopia changes, but we are already seeing it with AI slop coming to dominate the internet. It comes down to consumers to refuse to eat at those troughs. But if they do (and we see that trend, sadly) we will see more AI slop dominating books and writing.

Off-topic: I like seeing the human hand in text: typos, misused words, spelling mistakes, and other signs of a person behind the text. I used to feel annoyed when I stumbled across such problems in books. But with the pristine, sterile text LLMs and grammar tools produce, I now appreciate these human mistakes.

We may see more obscure manga, obscure outside of Japan anyway, that may not be profitable without machine-translation tools. Faster and wider releases benefit manga readers by increasing accessibility in their native languages. Piracy may decrease because it would lose its necessity. Former fan-scanlators may find work in the publishing industry with Mantra Engine’s remote work design. However, LLMs might also cost translator jobs, decrease manga quality, and push open the door to the publishing industry producing machine-generated manga. But it’s still too early to predict exactly how this software will change how the manga industry functions and how we consume manga. It’s even possible LLMs may be relegated to small tools or disappear because they aren’t as useful as they first appear, or because people prefer not to use them. This is the scenario I prefer. The software is too new for us to know where it will go, if anywhere, over the long term. People appreciate and value the human hand in stories. Don’t underestimate the power of voting with your wallet. That includes refraining from pirating manga because piracy is one of the motivators behind the development of machine translation tools. Use your public library or a legitimate subscription service instead.

References

Kuchitaka, Mitsuki (2023) The AI-Powered Manga Translation Service Sharing Beloved Titles with the World. KIZUNA https://www.japan.go.jp/kizuna/2023/02/manga_translation_service.html.

Schley, Matt (2023) Ancient Magus’ Bride Manga Reveals AI-Translated English Release. Otaku USA Magazine. https://otakuusamagazine.com/ancient-magus-bride-manga-ai-translated-english-release/.

My mom was a Japanese/American-English business and diplomatic interpreter and translator. I never understood how she could flow between the two languages. But she made it clear that translation is not the same as interpretation. And in Japanese speech, as much is stated by context and facial expression as by words… a constant problem for me. 😬 (I just realized how that works into those exaggerated manga and anime expressions.)

During long flights back from Japan to the US, I’ll occasionally occupy myself with trying to meaningfully translate a Japanese song’s lyrics into English. Ignoring things like meter and rhythm, I’ve come across a few that I thought were un-translatable. One reason is that spoken Japanese doesn’t really have very many sounds; so there are a lot of homophones. For example, in a song called “Rain” that’s really about tears of betrayal, there’s a line that reads in phonetic hiragana, “そっとうずくまて” (so tto u zu ku ma te). In the context of the song, it translates as describing a raining sky as “kneeling down gently”. But it’s also a homophone that, “a soft aching awaits”, alluding to the pain about to be released in the rain of tears that the song is really about. How can that be translated, even by an LLM.?

Another problem is simply what you note in the “feel” of certain idiomatic expressions. A song described accumulating loss and sadness as a love relationship slowly fades away, and the troublesome effect of the truth becoming increasingly apparent. But translating to English, the description of accumulating emotions bursting forth came across as something like the result of a festering infection, and ended up sounding… well, just gross. And that wasn’t the feeling of the piece of music at all in Japanese, where it felt more like being emotionally deflated by the disappointment. To communicate the actual feel in English, the words would need to be completely changed. An “interpretation”, perhaps? But not a valid translation.

I’ve seen the old Meiji period discussions about the Japanese language and writing system beginning to reopen. As Japan struggles with a declining population, some argue the language is a unnecessary barrier for immigration and complicates Japan’s cultural exports as you point out. Some of the old ideas of the inferiority of the Japanese language looks to be resurfacing, using the same arguments I’ve encountered in Meiji literature. It’s the old high-context versus low-context arguments. LLMs struggle with low-context language, and it’s worse with high-context languages like Japanese for the reasons you point out!

Resonant Arc has a great interview with the game translator Alexander O. Smith where they discuss the problems of translation versus interpretation and how accuracy in contexts like you describe requires interpretation and not simply word and phrase translations. Here’s one of their interviews:

Interpretation can foist the translator’s perspective on people, but a literal translation can distort as you point out with your experiences translating song imagery.

When reworking Edwardian and Victorian language into modern English, the same problems can appear because of the cultural contexts. And that’s within the same language! When crossing cultures, languages, and time periods the process gets even harder.

Watching a bit of the video, it reminded me of a Japanese film dialogue translation/re-interpretation into English that I once encountered in Haruki Kadokawa’s, “Ten to Chi to” (天と地と), about the battles of Kawanakajima. There’s a (historically-based but fictionalized) but very moving scene where an onna-musha, “Lady Yae”, leads her group of warriors to a position at a stalled battle front at a river crossing where her troops perform a display of skill for the Lord Kagetora and his generals who are atop a low hill on the other side of the river. Then, she challenges any taker with the courage to a duel. However, the only response is a taunt from one of the generals that perhaps he would “challenge her in the bedroom”, which elicits laughter from all but Lord Kagetora. He recognizes her courage. But he also recognizes that the ridicule has left her dishonored.

At this point, a Japanese viewer with any historical knowledge of the events being depicted understands that Lady Yae’s next action is effectively committing suicide. She rides her horse into the river… into the range of Kagetora’s arquebus. And reluctantly, he carefully aims and shoots her off her horse.

In the Japanese dialogue that follows, it’s understood that both Lord Kagetora’s and Lady Yae’s honors have been maintained, Kagetora by his marksmanship, and Yae by her courage. And it’s understood in the following scene that her body is thus being returned with proper ceremony. In the English-dubbed translation, however, a general simply calls her “foolish”.

I think that whoever did the translation probably just figured that an English-speaking audience simply wouldn’t get the point of the scene. The Battles of Nakajima are recalled as feudal conflicts that utterly decimated both armies without ever producing any clear victor. And they also marked a point in Japanese history where the introduction of firearms changed the place of honor in battle… face-to-face courage versus pragmatic utility. And this was the whole point of the film… What is the value of courage in a utilitarian world?

It’s interesting how the choice of using the English word “foolish” changes the point of the film. The word acts as a general commentary about the war and the “foolish” waste of life instead of pointing out the honor aspect you discuss. It makes me consider the idea that once a creative work has been released, the meaning of the work no longer belongs to the producer of the work but to the viewer.

AI translation is extremely likely to take over. A purpose-trained model can be fed all of the previously translated idiomatic expressions and other sources you can get your hands on. A more advanced translation tool utilizing the model could actually look ahead and behind so that instead of merely translating text one bubble at a time, it takes into account information from other pages to keep names and other details internally consistent.

Will it help defeat piracy? I doubt it. If these tools are perfected, scanlators can boost the speed of their own release output just as well as the official translators can.

And that’s only if you expect some polishing of the results. If you can distribute the tools to everyone, anyone can translate it on their own computer. This could be packaged as an application or browser extension that can translate a manga chapter with a button press, or even automatically, just as browsers already automatically detect foreign language websites and give a one-click option to translate the text. Translation will become completely decentralized, meaning you just need to navigate to or download the raws. Even if Japan or Korea got ten times better at taking down easily accessible raw sites, you could distribute the image files through onion sites, torrents, or other methods.

On the back end, AI translation quality will continue to slowly improve until it completely plateaus, and on the front end, a good user interface experience can be developed once and locked in.

You are right. Once Mantra Engine and other manga-translation models get into the wild, piracy would likely increase. But it also opens the doors for more indie manga creators to produce works for the international market. But piracy isn’t a victimless crime. It hurts mangaka and publishers. There’s evidence that points toward piracy as a discovery tool and so enable reader buying authors they wouldn’t otherwise. But this doesn’t balance the lost income. Mangaka already face difficult work environments and low-incomes, just as book authors do. Few rise to the top. LLMs have damaged the market value of writing and art and the services that surround them.