A day divided into 24 hours of 60 minutes, which are each 60 seconds in length, feels natural. But at one time, daylight didn’t divide so mechanically. Many mistakenly think people didn’t care about timekeeping even just a century-and-a-half ago. The idea: agriculturally based economies didn’t need hourly timekeeping and instead focused on seasonal and monthly timekeeping. However, sundials and other methods of timekeeping were common to time plantings, festivals, and other tasks.

We also consider time zones that vary as we move from the Prime Meridian which is near Greenwich, or more accurately the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) Reference Meridian, natural. But before 1884, each nation set their meridian (which denotes 0° longitude for navigation in addition acting as a calibration time for a nation’s clocks) at, usually, their capital cities. France used Paris; England, however, used Greenwich which isn’t far from the current Reference Meridian (Frumer, 2019). During the Meiji Restoration, Japan debated about moving their meridian from Edo to Kyoto. In 1861, Fujino Masahiro wrote:

Although our country should certainly measure its degrees relative to Kyoto, our countrymen have not yet sailed abroad and therefore have not measured the longitudes and latitudes of various places. Meanwhile, we use the longitudes and latitudes determined in England, and only after taking this as a our reference point, calculate the longitude of Kyoto.

The placement of the Prime Meridian matters for precise time measurements. Pendulum clocks need a calibration point, usually using local noon. The longitude difference among these calibration points have to be considered when dealing with time-space measurements, such as when you need precise navigation or geo-astronomically precise maps. Mechanical clocks became vital for navigation and other tasks. When UTC, coordinated universal time, settled on marking time 00:00 at midnight in Greenwich and then mathematically dividing the world into standard time zones, Japan adopted the practice. The difference from their Kyoto-calibrated timekeeping worked out to be about 3 minutes which was good enough for most daily tasks. Time as we know it had a lot of variability.

Japan took timekeeping for granted. And this wasn’t an artifact of Japan’s modernization during the Meiji period. Japan had its own timekeeping system long before the Edo period. By 1884, mechanical clocks were already an important part of Japanese culture. Oh, and if you are wondering about latitude, the Earth’s equator serves as a natural 0° line. The Earth’s longitude, however, didn’t have or, up to that period, needed as clear a 0° line.

The Gift of Mechanized Time

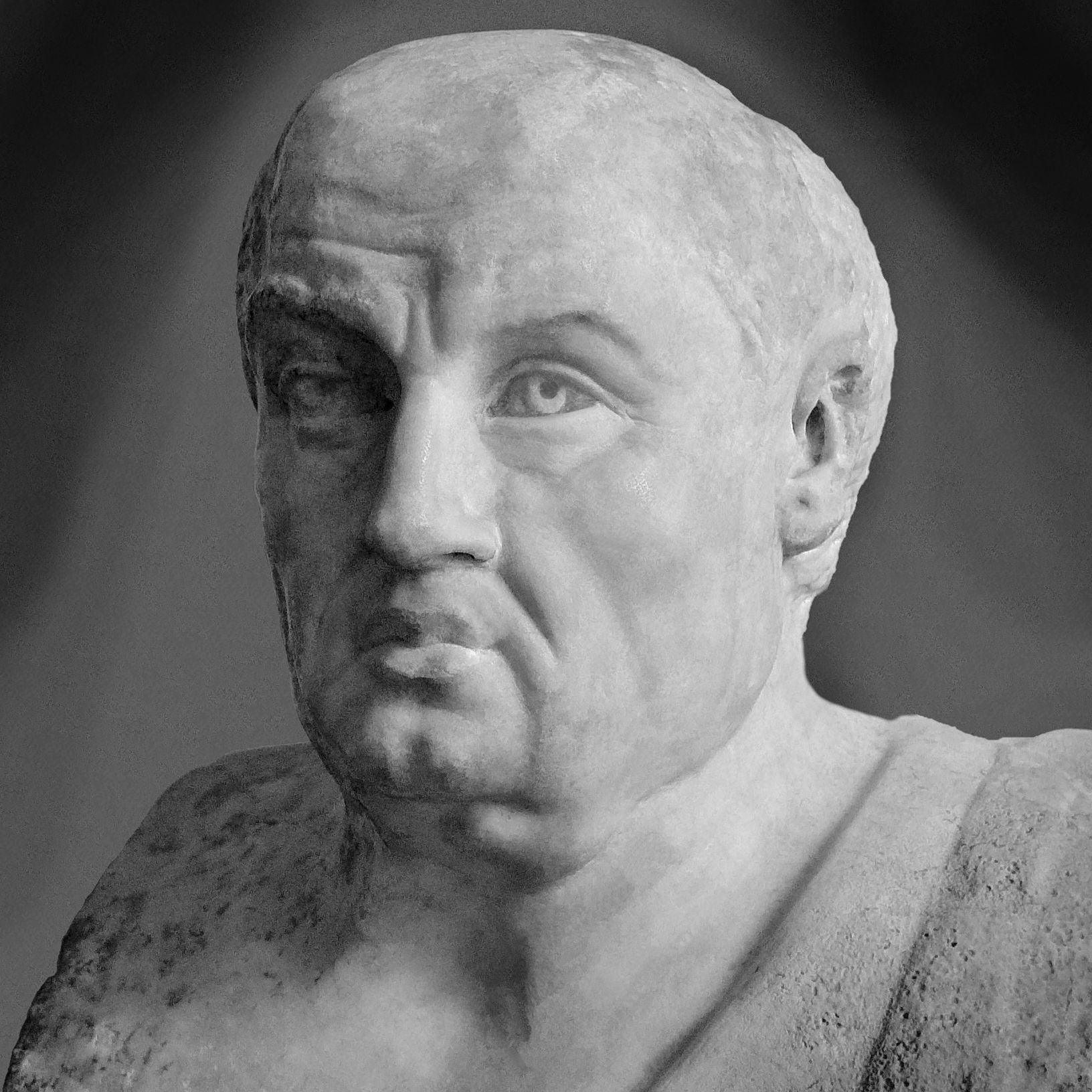

Long before humans became enslaved to the mechanical clock, clocks were used as expensive and exotic gifts. Jesuit missionaries made gifting clocks to rulers a central practice for their work. The Jesuits, also known as The Society of Jesus and as the Jesuit Order, acted as the arm of the Catholic Church which evangelized and brought Christian education to non-Christian nations. When Francis Xavier, the first Christian missionary to enter Japan, arrived, he presented Ouchi Yoshitaka, the lord of Suo Province a mechanical clock in 1551. The Portuguese Jesuit Luis Fois described the clock as “an exquisitely made striking clock” and Ouchi’s biography’s description of the clock as the first appearance of such a device in Japanese sources (Hiraoka, 2020):

Among the various gifts offered by the man from India was [a device] that showed the invariable length of day and night when ticking away twelve periods, ringing a bell that played tunes of five and twelve scale tones without needing to pluck the thirteen strings of a koto.

Xavier started a practice that other Jesuits visiting Japan’s rulers followed. Frois brought a clock to his audience with Oda Nobunaga, who appeared to be quite interested in the device. Nobunaga’s retainer, Wada, supported the Christian missionaries and tried to use clocks to encourage people to visit the Jesuits and hear their sermons. An astronomical clock, showing the phases of the moon and the daily path of the sun, was built at the Assumption of Mary Church in Nagasaki in 1603. Despite his enthusiasm and support for the Jesuits, Wada didn’t become a Christian. Frois wrote of Wada in his work Historia de Japam as Hiraoka (2020) cites:

[Wada] told the Father [Frois] to come with him [to meet Nobunaga] and to bring with him the small striking clock of exquisite mechanism that the priest had shown him before, for he had mentioned it to Nobunaga, and he very much wished to see it. They [Frois and Japanese Brother Lorenzo] went and found him [Nobunaga] with only a few gentlemen in attendance. He saw the clock with great admiration and said to the priest, who offered several times to send it to him as a gift: “I do wish very much to have it. However, I do not want it because it would be wasted on me” [which he said] because he felt it would be difficult to adjust it. […] He would then spend two hours asking the Father and Brother Lorenzo about Europe and India, while the Lord Wada, stayed outside on a veranda on his knees, helping with everything he could.

Alessandro Valiagnano brought his own clocks to Nobunaga and, later, to Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Japan’s shogun didn’t seem to tire of these gifts. Hideyoshi summoned Joao Rodrigues to teach him how to adjust the clock, and the Annual Report of 1581 states:

One day Nobunaga suddenly visited our residence and he came upon the Fathers before they knew of his arrival. [..] Nobunaga kept his attendants on the lower floor of the residence and went up to the top floor, and spoke to the Fathers and the Brothers with great affection and familiarity, and went to see the clock, and also saw a clavier and a viola that we had in the house, and he had someone play both, listening to them with pleasure.

The Jesuits began teaching Japanese craftsmen in how to make their own mechanical clocks in Nagasaki, and soon native clockmaking became a business of itself. Tokugawa Hidetada even used mechanical clocks to organize his daily life. In a fun anecdote, one time his attendants stopped the clock from ringing when Hidetada’s meal time had gone past the set time. They were admonished for not following the clock.

When Japan cracked down on Christianity, many clockmakers ran afoul of the government because of their close association with the Jesuits. Records show one Japanese-Christian clockmaker survived the purge, Tokei Seizaemon (The Clock Seizaemon). His master was a Christian and so Seizaemon became one too. After he left his master’s workshop, he returned to Buddhism but was still imprisoned based on suspicions about his Christianity in 1645. He was released in 1654.

Before the Jesuits brought their mechanical clocks, Japanese people already used stationary and portable sundials, clepsydras (water clocks), sand clocks, candlesticks, and incense clocks. And these weren’t inferior to the Western mechanical clock. In many ways, they were more accurate, and Japanese clock makers merged these traditional timekeeping methods with Western clock-making techniques. This allowed Western-inspired clocks to trickle down the social ladder until Japanese clocks became commonplace in the Edo period. Frumer (2014) reminds us:

To modern readers, understanding a clock seems almost intuitive; we think of a clock dial as self-explanatory and rather simple. Yet for somebody who has not had the experience of using a Western clock, the information contained on the clock face could be simply overwhelming, and there was nothing obvious about the logic of reading Western time.

Starting in the 1820s, it became fashionable to carry Western pocket watches (Frumer, 2014):

Japanese consumers in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries already saw mechanical clocks as the pinnacle of mechanical ingenuity. Combined with a kind of utopian vision of the West as efficient, calculated, productive, and lacking wastefulness, this perception of Western clocks produced an image of mathematical rationality and economic efficiency.

Much has been written about Orientalism in the West; Japan also looked at the West in similar ways. The clock became as representative of their view of the West as Madam Butterfly became a representation of the West’s view of Japan.

Animals, Bells, and the Shrinking-Stretching Hour

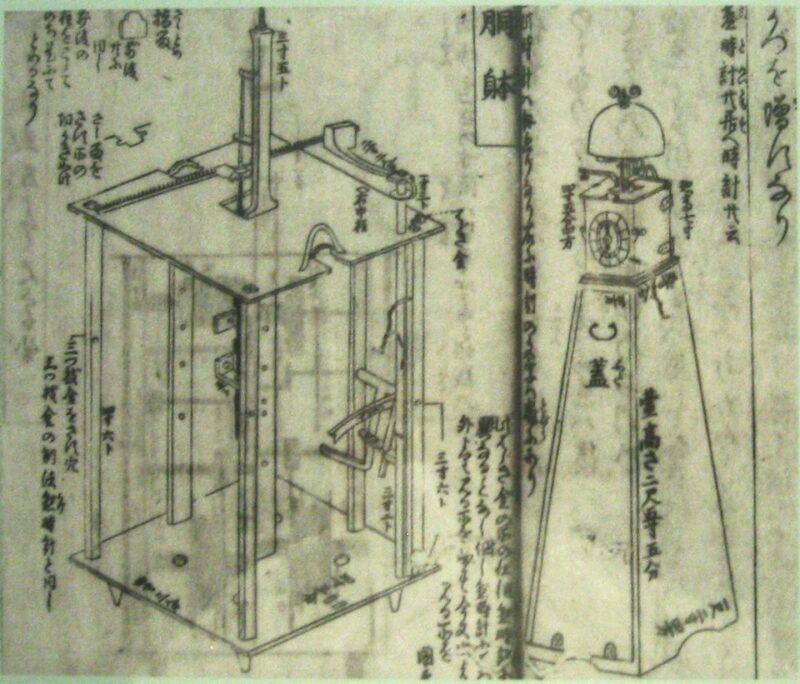

Japan’s traditional timekeeping system made early Western clocks useless until Japanese clock makers adapted them. The failure of the Western clock to reflect the seasonal changes in the length of the day caused confusion. The hours were deemed unstable, much as we considering the “variable” hours of the seasonal time system unstable. Japan’s traditional timekeeping system followed the change of sunlight across each season. The system used two methods to designate the hours: twelve animal signs and a number system. Each hour had an animal sign: the rat marked midnight, the horse marked noon, and so on. Numbers were used to mark the hours via bell strikes. The numbers didn’t follow the familiar ascendant number system of 1 through 12. Rather, they followed two descending series that ran from 9 to 4. Midnight would have 9 bell strikes, and so on until you hit 4 bell strikes at 11 AM. The numbers would reset with noon having 9 bell strikes and 11 PM having 4 strikes (Frumer, 2014). These bell strikes helped regulate daily work and festival timing.

The length of each hour varied by season. Frumer (2014) writes:

At that time, the day in Japan was divided into two parts: daylight and darkness, defined by dawn and dusk. Each of the periods lasted six “hours,” but since the relative length of light and darkness changed throughout the year, the relative length of these “hours” changed too, so that one hour could be as long as 155.952 modern-day minutes or as short as 76.75.

Work contracts indicated working hours by season and how much would be paid for overtime. Work contracts also outlined how much pay would be cut from a tardy worker. This shows just how important timekeeping mattered for Japan even when it was largely agricultural. Frumer (2014) adds:

Concerned with knowing the time of the day, people increasingly used more and more timepieces, non-mechanical and mechanical alike, and in the first half the nineteenth century most urbanites carried some kind of portable measuring device.

When Japanese clockmakers replaced the numbers on the Western clock face with animal symbols, they put the midnight hour at the bottom of the dial, and worked out how to represent the variable hours. They handled this using weights to slow the clock’s mechanism and, more simply, kept the device’s steady speed and made the hour signs movable, allowing the user to increase or decrease the space allocated to an hour on the dial. This mimicked the nature of how sundial shadows varied with the seasons. Each year, the government issued calendars with astronomically calculated tables to allow people to calibrate their hours each season. Most people also had a general idea of how to calculate or set the hours for each season. Japanese clockmakers even worked out how to make solar graph-like clocks (ruler clocks).

Meiji restorationists, after 1873, decided to drop this old system and the fully adopt the Western timekeeping system. This took some time, but the transition had already been underway thanks to the widespread adoption of mechanical timepieces and the fashion of wearing Western timepieces. As people moved away from agriculture, the seasonal system lost its importance. In many ways, the traditional Japanese system better reflected the real experience of time than the rigid Western timekeeping system most everyone uses today.

References

Frumer, Yulia. (2014) Translating Time: Habits of Western-Style Timekeeping in Late Edo Japan. Technology and Culture. 55 (4) 785-820.

Frumer, Y. (2019). Kyoto and the heavens: setting Japan’s center of time. Japan Forum, 31(4), 511–531. https://doi-org.oh0164.oplin.org/10.1080/09555803.2019.1599984.

Hiraoka, Ryuji. (2020). Jesuits and Western Clock in Japan’s “Christian Century” (1549-c.1650). Journal of Jesuit Studies 7. doi :10.1163/22141332-00702004.