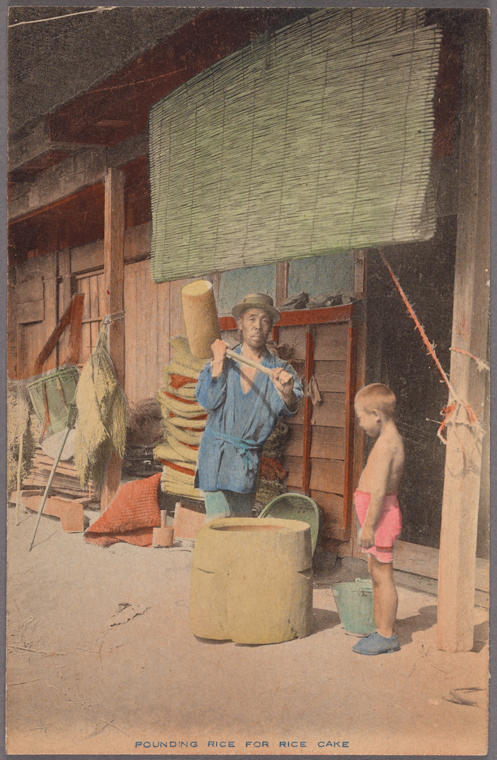

In Japan’s history, rice was once a currency and a commodity. Rice remains a staple grain throughout Japan and Asia. No doubt you’ve heard about Japan facing a shortfall of rice supply against their rice demand, causing prices to rise. But this problem has been gaining momentum since at least 2023 for a variety of reasons. In 2024, the price of a 60kg bag of rice rose to $160, a 55% increase over previous years (Lau, 2025). The shortage didn’t really hit until this year, prompting the Japanese government to release emergency rice stores in an effort to stabilize prices. But so far only 10% have reached the market. And the shortage has led to Agriculture Minister, Taku Eto, resigning after making an out-of-touch remark about how he “never had to buy rice” because his political supporters gifted him rice. “The remark was seen as utterly out of touch with the realities of ordinary people struggling to make ends meet and to afford rice to eat (Yamaguchi, 2025).”

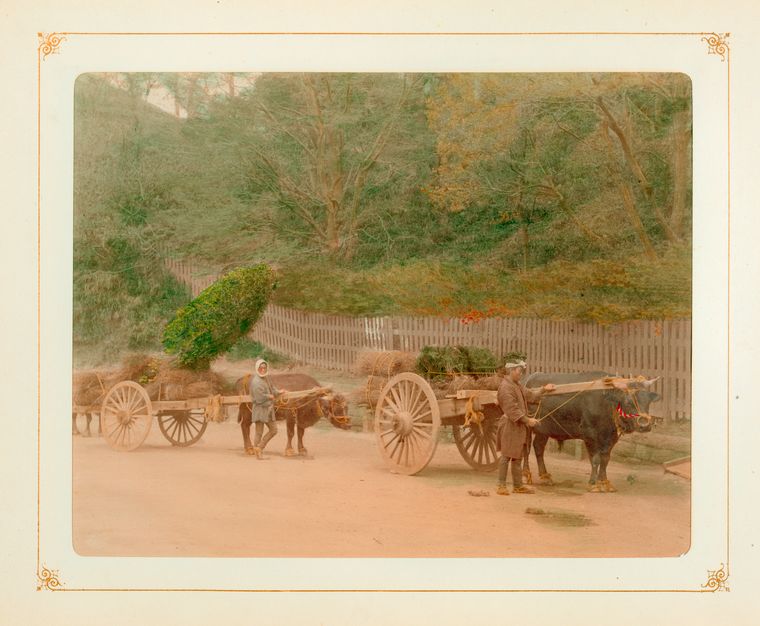

The demand for rice has been growing in Japan for a variety of reasons. In 2024, a warning about a possible megaquake sparked panic buying. A series of typhoons prompted more stockpiling and also damaging rice crops in 2024. Tourist demands for rice dishes like sushi and onigiri have added to demand. The Russia-Ukraine war along with a weakening yen has caused wheat prices to increase and other foreign import prices to also increase. This led to more people buying domestic food, including rice. On the supply side, The average age of farmers in Japan is 69 years old, and the number of farmers has been divided by half in the past 20 years. Japan’s government has paid farmers to cut back on rice acreage in favor of other crops. Typhoons have been damaging rice production for several years prior, and the increasing heat most countries in the world have experienced in recent years has impacted the quantity and quality of rice (Giseburt, 2024;NHK, 2024; Yamaguchi, 2025).

Japan, like most of the world, has endured record-breaking heat which contributes to a decrease in rice. Farmers have been introducing heat-resistant rice varieties in response, but many Japanese people are particular about their rice. Heat creates chalky grains which are fragile, leading to more milling loss and less favorable texture (Giseburt, 2024):

Harvests on Nagasaki Prefecture’s Tsushima island have also included more chalky grains than usual due to the heat, and farmers expressed concern about how their customers would react. “Will they think ‘This year’s rice is weird?’” says Yu Arikawa, a member of an ecologically minded farmers’ group on the island.

All of this adds up to the problems and political stirrings happening in Japan. But none of this has been sudden. Events tend to slowly creep until they hit the point they become a major problem. This rice shortage problem has been building for several years. This makes problems difficult to trace or predict because these slow building momentum problems often appear temporary at first. Other problems move so slowly that you can’t trace them until they reach their tipping point. The China-Taiwan issue in the news, for example, has been slowly building since Mao. Taiwan, if you aren’t aware, houses the government Mao and the Chinese Communist Party ousted. It isn’t the same government, but Taiwan is where China’s government had fled. As long as Taiwan exists, the CCP remains illegitimate. We are talking 76 years of slow momentum building.

In any case, Japan’s rice shortage will likely be among many future (and unseen present) shortages relating to increasing heat indices and shifts in rainfall across the world. Food prices will likely continue to increase because of how these events will continually hit supplies until demand outstrips the falling supply. Once this happens, prices will increase. Efforts to mitigate this, like farmers introducing heat-resistant rice, need similar time to gain momentum and acceptance. Of course, there’s also the debt cycle at play here, which underpins inflation. I suspect we are nearing the end of the debt cycle–the period in which debt must unwind–which will also impact prices. While the unwind is painful and often destructive (it doesn’t have to be either), it is a necessary and unavoidable part of the economic cycle. This appears to be a player in Japan’s rice prices because of how weak the yen has remained for decades and how that weakness has increased. But there are many variables behind this too. The weak yen makes it difficult to afford imports, but it helps Japan’s exports. If you are a foreigner earning yen, such as in the JET or some other language-teaching program, the exchange rate on your paycheck reduces your buying power outside of Japan. Conversely, if you have a means of income outside of Japan that pays in US dollars, Euros, or some other stronger currency, your buying power is greater.

In short, the rice shortage and price increase has been building over the past several years because of many different variables, and it will likely take a some time to unwind.

References

Giseburt, Annelise (2024) Climate change, chalky grains and the risks for Japan’s rice farmers. The Japan Times. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/environment/2024/04/28/climate-change/rice-climate-change-risk/

Lau, Chris, Ogura, Junko et al (2025) Rice crisis: Japan releases strategic reserves to ease prices of nation’s most important food. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2025/04/06/asia/rice-prices-japan-strategic-reserve-intl-hnk

NHK News (2024) Why Japan is running low on rice. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/backstories/3553/

Yamaguchi, Mari (2025) Emergency reserves, high prices, rationing. How did Japan’s rice crisis get this far? Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/japan-rice-explainer-shortages-rising-prices-agriculture-6e21bc9017c8f6d8c0a1f179e50e975f

This happens periodically. Part of the problem in Japan is the preference for starchy, short-grained rice. This causes longer-grain replacement varieties, and especially cheaper aromatics like Thai Jasmine to be unacceptable to Japanese tastes. Korean glutinous rice is about the only viable alternative to much restaurant or specialty cooking… but it’s also prized by Koreans, making it very expensive. Walk into a Japanese (or Korean) household and see the $500 rice-cooker, and you’ll understand.

There’s also an agricultural protection issue that’s built into Japanese politics that makes rice imports prohibitively expensive. This is largely a result of Japan’s constitutionally mandated disproportionate representation of rural regions, which also serves to keep the LDP in power. You won’t find many rice farmers willing to bite the hand that feeds, and that’s most farmers in Japan.

Thanks for the insights! The articles I read pointed toward that preference as making it harder for farmers to take up heat-resistant varieties. The preference, heating climate, and loss of farmers might make these shortages more regular, don’t you think?

Seems like about a five-year cycle… couldn’t say why. This time around is mostly just panic buying, like toilet paper in the US during the pandemic. It started with media warnings about being prepared for a “mega-quake” after prices had already been run up by seasonal shifts in production and tourist demand. Personally, I think there’s another reason for encouraging the stockpiling that may become apparent in the US soon. I don’t know about the need for heat-tolerant varieties… maybe a regional issue?