I enjoy a good yokai story, having studied yokai stories and even reworking versions of them for modern readers, freeing them from their late 1800s English and Latin (which were often the first time these Japanese stories were written down). If you are curious, I collected all of these into my Tales from Old Japan book. Anyway, when I saw This Monster Wants to Eat Me dealt with yokai, I was in!

But I wasn’t prepared for the story I encountered. Spoilers ahead.

Hinako wants to die, but she can’t bring herself to follow through with this desire. She had lost her family in an ocean accident, leaving her scarred and alone, tormented by survivor’s guilt and a deep depression. But a memory of what she believes are his mother’s final words urging her to live holds her back from ending her life. This memory doesn’t stop her from willingly offering her life to yokai (made from the souls lost at sea) on her way to school one day. The mermaid Shiori save her, saying she wants to eat Hinako when the time is right. Unbeknownst to Hinako at the time, they had already met during Hinako’s childhood. Shiori had given Hinako a bit of her blood, granting Hinako the power to heal quickly, and a blessing for Hinako to live well before removing Hinako’s memory of their meeting. The accident that claimed Hinako’s family happened not long after. Shiori’s mermaid blood allowed Hinako to survive. As the story progresses, Hinako learns that Shiori had lied about her initial promise to eat her. Any human who tasted a yokai’s blood becomes revolting to that yokai, and Shiori only wants Hinako to live. The words Hinako attributed to her mother were Shiori’s.

Hinako’s best friend, Miko, tries hard to cut through the survivor’s guilt and depression Hinako has. Miko feels responsible for the the death of Hinako’s family. Miko is a kitsune, chained long ago to the area and forced to live with humans for so long that she grows to like them instead of wanting to eat them as yokai do. She becomes a guardian deity. Her failure to prevent Hinako’s tragedy weighs on her, and she does all she can to ease Hinako’s despair and protect her from other yokai, yokai like Shiori. Hinako has a scent that draws yokai to her, stoking their hunger for her. This keeps Miko and Shiori busy protecting her.

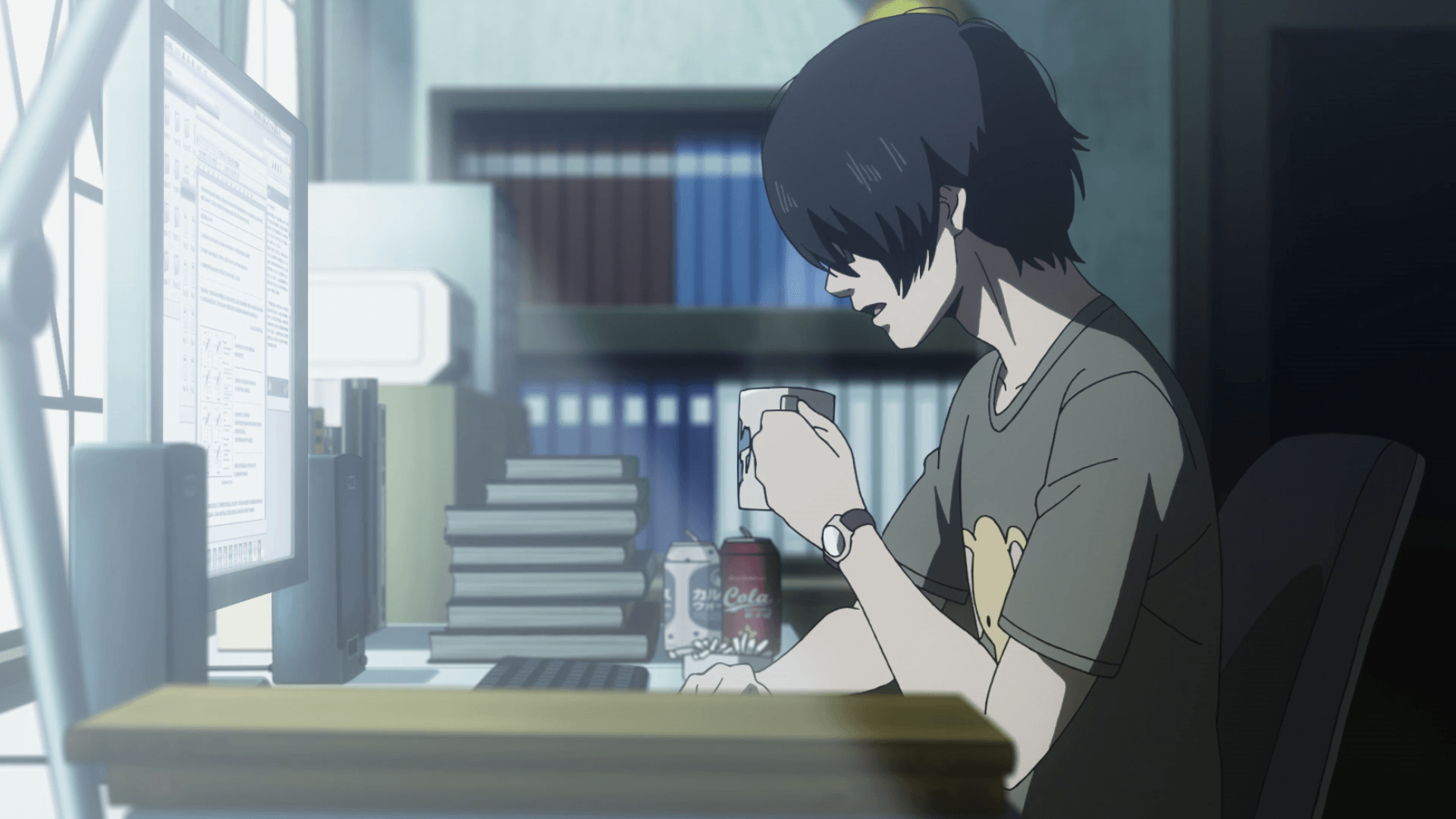

The story represents Hinako’s despair using undersea effects. Hinako feels as if a part of herself remains out at sea, with her family during the accident. She feels like she’s drowning in a dark sea, drifting alone. Miko’s over-the-top bubbliness sometimes offers a bit of light for Hinako to surface again, but Hinako never fully frees herself from her despair. It becomes a little easier after Shiori promises to kill and eat her, but Hinako rarely shakes her depression for long. She succeeds for short intervals after Shiori convinces her happiness would bring her closer to being eaten. Happiness and smiles are needed for Hinako to reach the height of her flavor, so to speak. It’s all a ruse to try to get Hinako to live, to be the little girl Shiori had met years before.

Miko and Shiori act as foils for each other. Miko, at first, believes Shiori is serious about eating Hinako and vows to stop her. At once point they fight with each other. Hinako’s scent almost drives Miko to eat her at one point. Despite Shiori’s promise, Hinako would’ve been glad to have Miko end her suffering. But Miko manages to stop herself by tearing off one of her own tails. Shiori doesn’t understand Miko going to such lengths. Miko had lived with humans for centuries and had largely tamed her yokai hunger. Shiori has only begun to live with humans thanks to Hinako. They enter a truce for the Hinako’s sake, and the truce slowly becomes a sort of friendship. Miko tries to explain humans to Shiori and the need to communicate. Shiori doesn’t understand how to begin talking with Hinako. The difficulty of it makes her believe communication isn’t valuable. In the end, Shiori renews a promise to eat Hinako, but she doesn’t promise when. Miko observes how much the promise hurts Shiori.

The story injects lighter-hearted scenes, particularly when Miko is involved, to balance the serious scenes. This contrast punctuates the psychological horror. Many horror stories make the mistaken of not introducing levity. Levity and rest periods of normalcy makes the horror elements more terrible through the contrast. From a visual standpoint, silly simplified “cards” like this one emphasizes the scenes lavished with frames, colors, and composition.

This Monster Wants to Eat Me is a dark story. Hinako’s despair, suspended between the desire to die but not doing the deed herself, speaks to the experiences many face. Women are more likely than men to hang in this limbo than men. Men more often give in to the despair and end themselves. The story examines the helplessness people can feel when seeing a loved one suffer as Hinako does. Miko and Shiori both struggle with this helplessness. Miko tries to pull Hinako into life through everyday joys like sweets and fun. Shiori enables Hinako’s despair with her promise to kill and eat her. That enablement pulls Hinako a little more to the surface than Miko’s efforts, but that enablement doesn’t heal the depression Hinako feels. Only after Shiori and Miko combine their efforts does Hinako start to emerge from the depths. Hinako comes to understand that Shiori and Miko are trying their best to save her. Shiori explains she only wants Hinako to be happy, and in the final episode Hinako decides to give up on her wish to die.

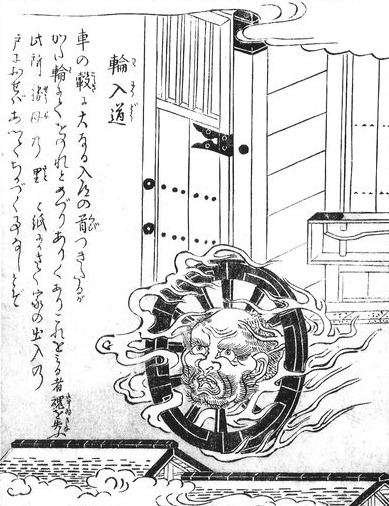

The story is a slow-burn psychological horror. The yokai that appear, including Shiori, add the visual horror elements. The foundation for the horror is Hinako’s torment and desire to die. Several times she gives herself over to Shiori and once to Miko in the hopes one of them will end her existential pain. She has no purpose, going through daily life in a monochrome malaise that many feel. She goes to school, cooks food (thanks to Miko’s lessons), and goes about the grind of daily life without any joy or heart. Her heart remains at the bottom of the ocean with her lost family until the finale. The story points to how no one can pull someone from their despair. Nothing Shiori or Miko do truly helps Hinako until she decides to change. Mental health improvement requires outside support but also the effort of the person suffering from the mental health issues. The outside support can only do so much. The sufferer is the only one who can do the work of healing. By the final episode, Hinako isn’t healed, but she decides to take the first step toward healing.

This Monster Wants to Eat Me has yuri elements in addition to the horror elements, but the mental health exploration takes the emphasis away from the romantic elements. The story unfolds slowly, turning like a wheel with its repeated plot elements while moving the story down the road. The animation and visuals reflects the melancholy Hinako feels and the slow, trapped feeling she has. Some may find the story too slow for their taste, especially with how it turns over the same spot of road a few times before moving forward. I found the slowness representative of how depression feels, of turning the wheel with the sense of moving nowhere even though progress is being made. The slow pace lends realism to the depression and relationship dynamics while emphasizing the psychological horror elements.This Monster Wants to Eat Me is an interesting watch, but its exploration of mental health and slow pace won’t be for everyone.

I’ve mentioned before that the creators of these kinds of anime seem to hide things about the characters in their names. Many kanji are, or would be (if it was appropriate) used in names with on’yomi or abbreviated kun’yomi pronunciations. At any rate, it struck me right away that there’s a hidden water theme in the names, as well as perhaps some clues to the characters:

Shiori (栞) is a route marker, a broken branch to show a trail, or a bookmark.

“Shi” (死) is death. “Ori” (折) at the proper time.

“Shio (汐) is the evening tide (a “water” kanji). “Ri” (利) benefit, or “Ri” (里) a “sato” or one’s native place, or “Ri” (狸) a “tanuki” or a cunning person, or “Ri” (理) the reason or the truth.

Hinako (鄙子) a faraway, distant, or ignorant child.

“Hi” (氷) ice, “na” (名) reputation, “ko” (古) “inishe” from an ancient time.

“Miko” (神子) is a shrine maiden. But…

“Miko” (水子) “mizuko” water-child, a newborn, a lost baby, or a stillbirth. Or…

“Mi” (海) “umi” sea as used in a name.

Thank you for this analysis! Manga and anime stories can have a lot of depth and layering with their character names and visual symbolism. It’s interesting how, as anime has become an international medium, Japanese symbology appears in American content and how Western symbology appears in Japanese stories. I find the German and Nordic elements especially interesting.