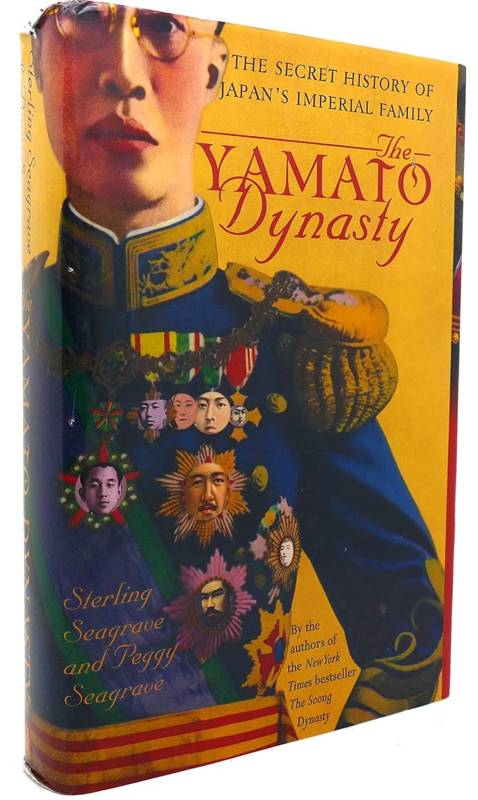

The Yamato Dynasty traces the Japanese imperial family from Emperor Meiji and the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate to Akihito. As you can imagine, most of the book centers on Emperor Hirohito. After all, he was Japan’s longest-serving emperor. To the authors’ credit, they spend a nice number of words on more obscure aspects of the imperial family.

For example, there’s a chapter titled “Bismarck’s Mustache” that examines how much influence Prussia and Otto von Bismark had on Japan. Prussia provided the standard for Japan’s reformed military post-Restoration. Bismarck, in turn, provided a western example of a strong leader:

Within one generation Japan did transform itself into a world power militarily, accompanied by astonishing industrial and financial development, but politically it took refuge in a rigid Prussian system that was modern only in costume. Bismarck made sure non of Prussia’s democratic institutions could seriously challenge his autocratic rule. Ito [Hirobumi]’s Japan would look similarly modern; its structure would have a democratic facade, but the windows and doors would be nailed shut. There would be an elected assembly, the Diet, where politicians could blow off steam, but they would be controlled by an executive responsible only to the emperor, who could never be challenged because he was divine. The emperor, in turn, would have his decisions made for him by a group of advisors, the State Council, ruled by the dominant clique. The leader of this clique would guide the emperor in the same way that Bismarck guided the kaiser.

Throughout the book, you will see these layers of window dressing surrounding the emperor’s authority. The authors make great pains in the final chapters to illustrate how these layers still exist in modern Japan. Vested interests sit behind politicians and make the decisions. This isn’t always the case, as the authors point out, but it exists beside the official democratic system. Japan has had this authority structure since its beginning as a nation. During the Heian period, an emperor would retire but still retain power. The sitting emperor would be stuck doing the formal rituals that came with the office. Behind the retired emperor sat the Fujiwara family, who gave the retired emperor only the decision options they approved. Time-to-time this would centralize, such as when Tokugawa Ieyasu took over the country, but the layers of power and illusions of power reasserted themselves.

General MacArthur and the American Occupation used these layers and was manipulated by these layers at the end of World War II:

As [Joe] Grew explained it to new president Truman, “The idea of depriving the Japanese of their emperor and emperorship is unsound for the reason that the moment our backs are turned (and we cannot afford to occupy Japan permanently) the Japanese would undoubtedly put the emperor and emperorship back again. From the long range point of view the best that we can hope for in Japan is the development of a constitutional monarchy, experience having shown that democracy in Japan would never work.”

The American Occupation doubted they would succeed without the emperor. MacArthur and the Occupation worked with the Imperial Artifice (my phrase, not the author’s) to paint Hirohito in that light because of this assumption. For the Imperial Artifice, it retained their existing power system and helped them mitigate the American’s reforms. The Seagraves spend many chapters describing the Golden Lily project and the interplay between the Occupation and the Imperial Artifice. According to the authors’ research, Hirohito wasn’t sheltered or complacent of the various war crimes Japan had committed, such as the Rape of Nanking, the Golden Lily project, or the human experimentation the Japanese military did. Hirohito, for his part, had been involved in some of the decisions. His family had been behind or involved in many of the crimes. The Americans also knew of the crimes but only allowed for window-dressing trials instead of something as thorough as the Nuremberg Trials.

For perspective, the authors account of sources that state yakaza Yoshio Kodama used his share Golden Lily wealth to bribe the US:

SCAP estimated Kodama’s worth in 1945 to be $13.5 billion (probably only a small portion of the actual total). Kodama only admitted publicly to having $200 million, and generously offered to give all of that to SCAP to split between America’s friend, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, and the Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC), a forerunner of the CIA. When Washington secretly accepted Kodama’s offer, Kodama and Kishi were quietly released from Sugamo and were never prosecuted for their leading roles in the dark side of the war. The American CIC was so appreciative of this $200 million bribe that Kodama was later hired as an expert on Red-bashing during the Korean War. He remained on the CIA-payroll until the Lockheed scandal in the 1970s.

Okay, so what was Golden Lily? According to the book, Golden Lily was the effort to strip Manchuria of its wealth, hide it, and transfer it back to Japan. Gold and silver was collected throughout the occupied territory before Japan lost the war, melted into bars, and then hidden in various locations while the wealth waited for transport. The Philippines proved to be the most common vault. This money then was channeled to the Americans and also used to create the “Japanese economic miracle” after the war and occupation ended:

Then there was Golden Lily, which was dedicated only to so-called “imperial” loot–plundered treasure that was collected, inventories and set aside for the imperial family. If Golden Lily did hide considerably more than $100 billion worth of this treasure in the Philippines, than the claim of postwar insolvency is rather suspect.

Golden Lily and the hidden men behind Hirohito become a focus of the writers, to the point where the book becomes more focused on this than the imperial family. Granted, the hidden men and hidden projects entwined closely with the family. The book is complex with how it seeks to disentangle all the knots and layers that surround the imperial family and World War II. But the number of actors involved can become difficult to juggle. Despite being named The Yamato Dynasty, the book zeroes in on Hirohito and the war. While World War II is a pivotal moment in world history and Hirohito is the longest-sitting emperor, the book is another World War II book. Interesting, but I would’ve liked more information about the early Meiji emperors. But I’m burned out about World War II. If you walk into an American bookstore or public library and go into the history section, you’d be convinced history didn’t exist before World War II. The war dominates those shelves.

If you aren’t familiar with the way the Japanese imperial system worked, interested in World War II’s Pacific theater, or interested in understanding the modern history of Japan, The Yamato Dynasty provides an interesting read. The book goes far into the weeds, further than I could summarize here, of Japan’s layers of artifice and mirrors. The authors include extensive notes and source citations to back up their arguments and reveals. The complexity of the book, however, had me stopping and re-reading a few sections to keep all the actors and events straight. This isn’t for casual readers, but people who enjoy deeper history, especially of World War II, may find this book interesting.

“Yamashita’s gold”… There was certainly some war loot. But it’s a story that sounds a bit like reading golden tea leaves.

My mom was a good reference regarding events at the end of WWII. MacArthur eventually realized that he was being strung along by established family powers looking to maintain imperial structure for their own financial benefit. So he ended up turning to several popular progressive Japanese legal scholars in writing a new constitution, and then bulldozed through an American-written draft by implying their support in newspaper releases.

It was also probably wise not to have killed Hirohito. It had been contemplated that if the atomic bombs were to become an every ten-day event (the rate at which plutonium devices could be constructed), the Imperial Palace would eventually be targeted. But Hirohito’s status ended up being instrumental in bringing down a military coup attempted by Imperial Army officers on the night before the surrender announcement. General Shizuichi Tanaka of Eastern District Army was able to end it merely by berated the officers involved for disgracing the Emperor, after which four of the six summarily committed suicide. Such was the sense of commitment and of loyalty of those in the Japanese military, right up to the very end. Even General Tanaka committed suicide nine-days later, taking personal responsibility for his inability to defend the Imperial Palace.

Many of the book’s claims seemed a bit much at times, even with the authors’ interviews and sourcing. I’m sure you noticed my scattered “according to the book” to hedge.

The book does do a good job describing what your mom stated too. Many World War II books don’t like to illustrate how MacArthur, in the end, strong-armed everything. The book spends a fair number of pages discussing how Joe Grew worked to preserve Hirohito and counter the still-resistant military families. Whenever I read about all the accounts, like what you point out with General Shizuichi Tanaka, I think of the Genpei War’s similar tangled patterns of the various militaries and cult-of-personalities. History doesn’t repeat, but it follows patterns.

Japan’s gradual move into its present form wasn’t by any means smooth or instantaneous. Among the reasons my family left in ’75 was the political turbulence that marked the time… violent nationalist, leftist and communist movements, and a still struggling economy that had already consumed the lives of an entire generation. My dad was involved in Tokyo University protests, but objected to the violence of Zenkyōtō. And even after a generation, there were still extremist retro-nationalists with significant followings, like Yukio Mishima. Even today, stay in an APA hotel and you can read (in Japanese) the chain’s owner’s, Toshio Motoya’s, neo-nationalist version of Japanese history in books left in rooms. While not mainstream contemporary thinking by any means, it does represent a still simmering cultural undercurrent. So I wouldn’t be so quick to judge MacArthur’s conundrum out of context. I think he knew that he needed to seize the moment, or someone would step in to take the mantle.

I’ve read a fair bit about that period. For your parents to be there and involved, that is interesting! Yeah, I don’t judge MacArthur’s strong-arm tactics. Sometimes that’s the only method available to get something necessary accomplished. MacArthur also had personal political reasons for getting solid results, but that doesn’t diminish the utility of what he, Grew, and others managed to achieve.

Discussing this makes me want to revisit John Toland’s “The Rising Sun.” I found the 2 volume version when a state library was clearing out their warehouse.