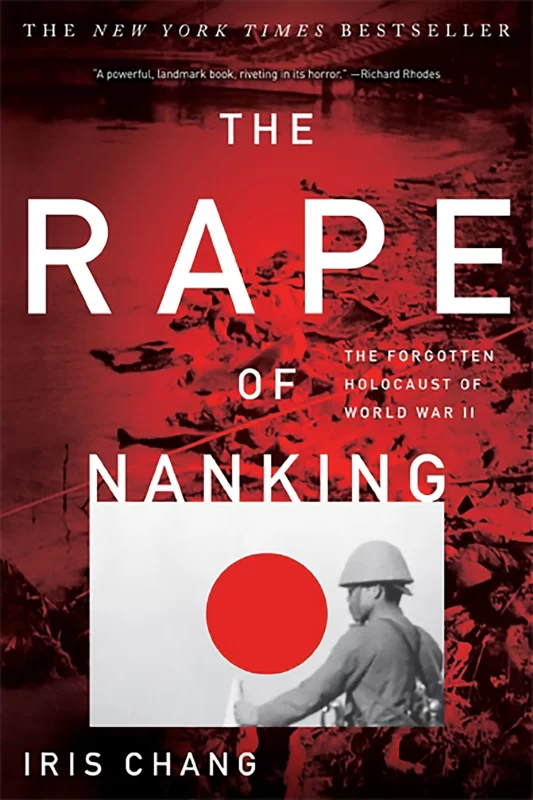

The Rape of Nanking covers the destruction of present-day Nanjing City by the Japanese during World War II. The book doesn’t hold back. In several chapters, I had to take a break from the relentless atrocities the author accounted.

The Rape of Nanking covers the destruction of present-day Nanjing City by the Japanese during World War II. The book doesn’t hold back. In several chapters, I had to take a break from the relentless atrocities the author accounted.

Nanking was the first area the Japanese went after taking Shanghai. The goal was to conquer China, and Japan has long had a desire to conquer China. Soon after becoming Shogun, Hideyoshi sent an invasion force into Korea with the goal of eventually taking China. The invasion failed. During World War II, Japan tried again, eventually occupying Manchuria.

The Rape of Nanking involved wholesale execution, torture, and rape of the populace. Japanese soldiers were trained to see the Chinese as less than human, as “pigs,” as they often called the Chinese. The Japanese soldiers would use Chinese men for bayonet practice, burn them alive, and hold beheading contests. The goal was to see who could behead the most in a period of time. As you can guess from the book’s title, women of all ages, including young girls, were raped. Chang wrote:

Chinese women were raped in all locations and at all hours. An estimated one-third of all rapes occurred during the day. Survivors even remember soldiers prying open the legs of victims to rape them in broad daylight, in the middle of the street, and in front of crowds of witnesses. No place was too sacred for rape. The Japanese attacked women in nunneries, churches, and Bible training schools. Seventeen soldiers raped one woman in succession in a seminary compound…

Old age was no concern to the Japanese. Matrons, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers endured repeated sexual assaults. A Japanese soldier who raped a woman of sixty was ordered to “clean the penis by her mouth.” When a woman of sixty-two protested to soldiers that she was too old for sex, they “rammed a stick up her instead.”

Chang goes on:

Little girls were raped so brutally that some could not walk for weeks afterward. Many required surgery; others died. Chinese witnesses saw Japanese rape girls under ten years of age in the streets and then slash them in half by sword. In some cases, the Japanese sliced open the vaginas of preteen girls in order to ravish them more effectively.

It was about here that I had to take a break from the chapter. Thankfully, she goes on to describe the efforts of Americans and Nazis and other foreigners to create a safety zone. She accounts how they saved women, men, and children from the madness by confronting the Japanese soldiers. They fended off raids by the Japanese against the safety zone and other trials. It is thanks to these foreign men and women that we know what happened. Most of Chang’s book pulls from their journals, photographs, and news reels. Yes, film of what happened exists and was smuggled out of Nanking. In fact, a copy of a news reel was even sent to Hitler, according to Chang’s research.

Whenever I read a book like this, whether it is about the Holocaust or the Rwanda genocide or events in Bosnia, I struggle. I struggle to believe such atrocities can happen. I struggle to understand how and why. The relentlessness of Chang’s account beggars belief. However, the destruction happened. The rapes happened. The murders happened. Chang touches on how in a section. Namely, the way the Japanese military was structured bred men who could rape and kill for fun. The training at the time was brutal. The brutality worked to empty the Japanese men of their humanity and to create a desire to get revenge for the abuse they endured. This doesn’t justify their actions, but it helps explain the psychology that led to atrocity. Dehumanizing the Chinese also helped them. Labels and language are powerful. They influence and reflect your view on the world. If the Chinese are less than pigs–after all, you can eat pigs–than it becomes easier to butcher them. The Japanese aren’t unique in this approach. Nazis dehumanized Jews, Gypsies, and their other victims. Likewise, colonial Americans dehumanized the Native Americans.

Dehumanization also combined with a feeling of exceptionalism. The combination of feeling superior to all others and the feeling of those others being a lower life form, allows people to do terrible things. Sometimes those terrible things don’t feel terrible, although Chang shares several accounts of Japanese soldiers who knew how they were being forced to lose their humanity. Yet, they also could do nothing about it.

The Rape of Nanking challenged me, as any book of its type does. I used to be able to read such books and watch bloody films without feeling troubled. However, as I age, I become more sensitive. Chang highlights an event that many have forgotten. Many history books merely mention it, focusing instead on what happened in Germany. Events in China were just as bad and deserve more coverage. Chang’s book reminds us of that.

Chang doesn’t go into it, but The Rape of Nanking shows the danger of dehumanizing people and having a misplaced sense of exceptionalism. The Internet and political discourse teems with these misconceptions. It’s dangerous. It takes little to push people over the edge and toward violence. We believe we can’t commit atrocities, but World War II revealed the banality of evil. It is a workaday event once certain thinking congeals. So even Internet dehumanizing can be dangerous.

So who should read The Rape of Nanking? History buffs, of course. But I also urge anyone who thinks Japan is “the best culture there is” to read it too. Chang did her homework well, as unbelievable as the World War II era can be. But be warned, it is a difficult, unrelenting read.

The author killed herself some time ago, perhaps because of the research surrounding the book.

I see that I read this and didn’t leave a comment. Please be careful with this kind of reading. There’s an internal boundary that has to be maintained. It’s important that these kinds of records exist; and it’s wise to have an understanding of this kind of history. But internalizing it can become self-destructive. I can’t imaging being Iris Chang. Less well known, the Japanese weren’t any better in the Philippines. I know a first hand story from Ponson Island.

I think you know that I lived in Phnom Penh in 2002, supervising a project at a prosthetics school. I consider myself a pretty resilient person. But returning to Thailand after six-months, I’d lost so much weight that my now-husband had a hard time recognizing me at the airport. “Revolutions” and “Barriers” were written from that perspective.

My dad was a pacifist, largely as a result of his childhood during WWII. He experienced how the terrible suffering that Japan had inflicted on others left the nation’s own population with no means with which to ask for mercy toward its own population. He taught me that *individuals* can suffer. But the civilizations that people build can’t themselves feel or understand suffering… or compassion. So it’s always the *individual* who bears the responsibility for his her own actions.

There’s a Japanese middle-school level book written by Kazumi Yumoto called “Natsu no Niwa” (Summer Garden)… I think there was an English translation called “Friends”. A main character in the story is an old recluse who is coming to the end of his life. But despite developing a friendship with three precocious twelve-year old boys who want to help him, there isn’t anything anyone can do for him. The boys eventually discover that what haunts this old man’s life is a moral injury. He returned from WWII with the memory of having killed a pregnant woman as she ran from him, and then watched as her baby died in her belly. It’s a gruesome and shocking moment for the reader. But it depicts how during collective brutality of warfare, an individual can still inflict inescapable injury upon his own character. Afterward, the man finds himself unable to return to his life or the woman he’d fallen in love with, forever replaying a moment of lost humanity in his own memories. In Asian culture, there is no “forgiveness of sin”. There is only that which one adds to his being through one’s actions in this world… for better, or for worse.

Moral injury is as real an injury as breaking an arm or something worse. Moral injuries also take longer to heal. You’re certainly right about the need to be cautious, retain boundaries, and not internalize content like this. I had been exposed to a lot of Holocaust footage and books, so I had thought myself “hardened” enough to read books like The Rape of Nanking. Thankfully, I learned I wasn’t hardened at all. You don’t want to be hardened.

Thank you for sharing your personal story and your dad’s perspective! And for sharing the Summer Garden summary. That sounds like a heavy story for middle schoolers.The Philippines’ experience under Japan during World War II is as horrific, even though it sees less reportage for some reason. Exposing yourself to books and footage that you are not equipped to deal with isn’t good for you.

There’s certainly no shame in avoiding such content. I’ve had to put down books about the Holocaust and the European theater of World War II many times before I finished them. I like to watch some fluffy, humorous anime or book whenever I’m reading such works.