The idol fandom–Japanese and Korean–has many different aspects that can be positive, neutral, and negative. I’ve written a few times about the negative side, and I will touch on that side again in this article. Everything positive has a negative side built into it. Understanding that negative side emphasizes the positive. Unlike anime and manga’s fandom, idol culture hasn’t been as well studied (Xu, 2022), and, when it has been studied, the academic literature focuses on the negative side.

Idol culture is a confluence of commercial interests, fan support, and the goals of the performers. Idol culture itself appears to be an international development. The word idol (aidoru) traces to a 1963 French film that circulated in Japan called Cherchez l’idole or Aidoru o Sagasu in Japanese. The film featured French pop singers and served something of a template for idols, with their ability to sing, act, and otherwise perform in many different areas of the entertainment industry. Some researchers link Japan’s idol culture as an outgrowth of the American Hollywood and music industry “star” system that sought to build a personal relationship with fans, starting especially in the 1930s. Bing Crosby works as an early American example of star/idol culture. Noémi Zs (2021) points out Hollywood and the music industry started to notice how:

The audience started to single out certain performers and wanted to put a name to these familiar faces, so they started to give performers nicknames (such as “the Biograph Girl” to Florence Lawrence, who is frequently referred to as the first movie star), and they were eager to know in advance which motion pictures would feature them.

This audience interest was also noticed by Japan’s developing cinema industry. In the 1950s, the Japanese industry took a similar approach to the American “star” system, in part because Japan’s first television networks relied on imported American programs to round out their domestic offerings.

As production of televisions brought the prices down, TVs became a part of the average family home, setting the environment for idols to develop. In the mid-1960s, Japanese studios began targeting teens with commercial pop music, such as the boy group The Johnnys. By 1971, the idol industry had about 700 idols debut, some of which were scouted for the show Sutā Tanjō (A Star is Born), that ran from 1971 to 1983. Idol agencies focused on creating new talent rather than relying on established entertainers, moving recruits from music to television. Noémi Zs (2021) continues:

Idols represented a whole new domain of stardom because they pose themselves not as extraordinary professionals but as one of their audience, the archetypal boys and girls next door, who are willing to compensate for their lack of outstanding talent with eagerness, hard work, and bright smiles. They are good-looking and can sing and dance, but only at a level that does not intimidate their audience. This way, the perceived distance between the performers and their fans is so small that their positions become interchangeable, and teen idols come to represent stars well within reach: since they are one of us, they symbolize what you too can aspire to be as an ordinary person with some hard work; therefore, their success is your potential success.

Because idols appear as boys and girls next door that make up for their “lack of talent” (they are usually talented) through hard work, enthusiasm, and smiles, the audience sees the distance between them and the idols as much smaller than with polished professionals. Idols are good looking and can sing and dance, but at an ability that doesn’t feel so far out of reach. Idols offer something fans can aspire to be with hard work–making fans wish for the idol’s success because of how it links with a fans’ potential success. The emotional connections between fans and idols and among idols themselves helps determine the success of the idol and all the business organizations behind the idol. Zhao (2022) observers that:

This emotional connection not only brings good commercial value and economic benefits. From a pop culture perspective, the emotional connection between fans and idols is equivalent to fans identifying with the values of their idols. In contrast, the image of a promising idol, in turn, shapes the values of the fans, and both sides can grow together.

The idol industry still capitalizes on this emotional connection. But following the heyday of the 1980s, idol popularity faded along with Japan’s popped economic bubble in the 1990s, but some idol groups managed to remain popular, such as SMAP, “Sports Music Assemble People.” Fast forward to today, and idol culture sees an international resurgence. The center of idol culture has shifted a bit toward South Korea with the enormous popularity of K-pop idols in the West.

Idols have long been associated with teen culture, and the traditionally short careers idols have adds to this association. However, Noémi Zs points out that many idols, particularly male idols, enjoy long careers and popularity, aging with their audience while often still appealing to younger audiences. Senior citizens can also become idols, such as KGB84. And AKB48, like most female idol groups, is marketed toward men aged between 20 to mid-60s (Lin, n.d.; Noémi Zs, 2021).

The Directionality of Idol Fandom

In Europe and the United States, an idol is an abstraction, in part thanks to “star” culture. It’s a one-directional relationship. This differs from the Japanese experience, where fans can join in an idol’s growth from audition to popularity. By the time the West learns about a Japanese or Korean idol, the idol is already big enough to present internationally. This adds to the apparent parasocial experience most Westerners have with idols. Westerners don’t have a chance to grow with the idol from music bar to star. I can’t discuss idol culture without touching on this parasocial dynamic.

Parasocial relationships are often understood as a negative experience in casual conversation. In academic studies, parasocial relationships are a natural outgrowth of how people relate to each other and toward ideas. It is neutral. Parasocial relationships can be positive or negative depending on the individual and depending on what the relationships foster. These interpersonal and parasocial relationships are not seen as opposite but rather a spectrum with various intermediate places a person could move within.

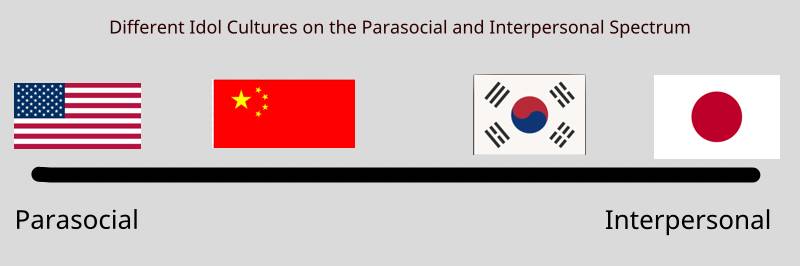

Idol culture appears to fall into a spectrum between interpersonal relationship and parasocial relationship, judging from what I’ve read in the limited academic literature. Interpersonal relationships are emotional ties between people who know each other. Parasocial relationship has a few varying definitions in academia. Generally, it is defined as a one-sided emotional tie to people you don’t know, know only through their public persona, or a fictional character. This relationship with idols is mediated in part by the greater culture the idol subculture sits within. The experience of idol culture in the United States, for instance, appears to be largely parasocial for reasons I’ve already mentioned. The experience of idol culture in Japan appears to be largely interpersonal, especially among upcoming idols and their fans. As idols became more popular, and their fans start to number in the thousands, the connections become more parasocial. Idols can’t connect one-on-one with their enormous numbers of fans on a true one-on-one basis after numbers hit a certain point. Dunbar’s number, for example, is a posited cognitive limit people have with relationships. Upcoming idols run into this limitation. As a person enters into more relationships, the amount of information and interactions to track grows exponentially, even for acquaintances. The Dunbar number sits at 150 with some people having more capability and some less. Not everyone agrees with the number or methodology.

South Korean appears to be closer to Japan than the American experience, and China appears to be closer to the American experience than the Japanese (Zhao, 2022). Of course, individual experiences will vary even more along this spectrum. It’s possible to have a parasocial relationship with an idol in Japan and an interpersonal relationship with an idol in the United States. The best American analog for the Japanese idol culture experience might be someone who follows a garage band or a music bar performer as they improve and sign on with a record label.

The industry itself leverages and encourages this relationship spectrum. The emotional connections between fans and idols and among idols themselves helps determine the success of the idol and all the business organizations behind the idol. But (Zhao, 2022):

The increasing commodification of fan practices threatens to erode the relationships and communities that have long been at their [idol culture’s] core.

The commodification allows idols to have careers and provide the fans with the method to offer their support, but it can also undermine the culture after a point.

The Benefits of Idol Culture

This brings me to the benefits of idol culture. The benefits stem from the interconnections between idols and their fans, their mutual symbiotic relationship. There are benefits even for those on the parasocial end of the scale.

Fans develop a connection to their favorite idols and with their fellow fans through materially supporting their idols by purchasing official products, by attending concerts and meetups, and by creating their own idol products. “Motivated by their admiration for idols, fans invest considerable personal energy and financial resources, using their contributions as a foundation for constructing their identities” (Wenbo, 2025). Fandom creates a self-identity and a sense of belonging for fans while building a commercial and personal identity for the idol. The level of involvement a fan has with the community of their favorite idol also influences the benefits they receive. More involvement and effort yields more happiness (Wenbo, 2025). Supporting an idol like this shows how interpersonal and parasocial relationships can be mutually beneficial when everything goes well. The more dedicated a person is, the more satisfaction and happiness they receive. But this sense of identity isn’t unique to idol culture:

Studies have demonstrated that football fans derive a deep sense of identity from their support of football clubs, which, in turn, elicits pride and accomplishment.

While this is all good, it also has a negative side where if something happens to the idol or to a person’s membership in the idol’s fan community, the fan can experience a loss of well-being, identity, suffer from depression or anxiety, and experience other problems. This shows how powerful the sense of belonging and idol support can be, just as powerful as supporting a sports team or football club. Wenbo notes:

Idols in the hearts of fans are not just performers or artists; they are significant pillars and sustenance of the fans’ spiritual life. In the eyes of fans, idols are often impeccable, worthy of admiration and following. However, when the idol suddenly falls from grace, this “collapse” phenomenon undoubtedly causes tremendous shock and destruction to the fans’ spiritual world, when idols interact with fans through social media, it not only enhances the fans’ sense of belonging but also builds the fans’ self-esteem.

The emotional connection brings commercial and economic value to the company, but the idol’s public identity, hobbies, and values help determine the fans’ own manners, hobbies, and values. Fans then reinforce the idol’s identity. Some consider it an idol’s responsibility to bring a positive influence to fans and guide them to a more moral and healthy life. In other words, being an idol fan encourages someone to become a better person. As Noémi Zs (2021) describes the relationship:

Most stars and celebrities appreciate and interact with their fans, but for idols, these relationships are truly paramount: their open dependence on their supporters is a central formula in their communication, and it distinguishes them from other tarento [talent]. Idol concerts and interviews usually feature lengthy speeches of gratitude where the teary-eyed performers reminisce over how they owe it all to their fans, whose unwavering support helped them reach their dreams and overcome all the difficulties they encountered on the way.

The centrality of this shared idol-fan relationship and the idol’s appreciation for their fans sets idols apart from other types of celebrities and enhances their ability to benefit each other. But as with everything, this can also work toward the negative. An idol may lead their fans to problematic identities, and their fans can lead an idol toward a ruinous identity. Fans could overspend in their support for an idol, and if an idol becomes disgraced in some way, fans may experience identity collapse as Noémi Zs describes. Reputation matters for a person’s well-being. Perceived reputation even predicts mental health problems. People who belong to groups that are sporty and fashionable enjoy higher reputation than other groups, such as idol and anime fans (Liu, 2022). However, this is more because of what society values than anything against anime or idol fandoms.

Idol culture also motivates people to learn Japanese or Korean, in the case of the K-pop fandom. This extends toward history, learning how to play an instrument, how to dance, how to sing, how to create art, and many other skills.

J-pop and K-pop Differences

In a survey of 350 Japanese university students, a few differences between J-pop and K-pop fans appear. The survey is too small to generalize, but the results remain interesting. J-pop fans tend to admire the human side of idols and their growth process.K-pop fans value the polished performances, visuals, and the public worldviews K-pop idols express. J-pop fans place a higher priority on supporting their favorite idols than K-pop fans. Their consumption preferences also differ in the survey: J-pop fans prefer in-person events where K-pop fans mainly engage through online consumption and interactions. This difference may be represented in the costs for concerts. Japanese idol tickets tend to be less expensive than K-pop tickets. Distance and financial constraints were cited as a factor for this difference in preference as well (Sakidachi Lab, 2025). But both fandoms experience similar feelings of belonging and mutual growth.

Ritual and Encouragement

Fans perform together in rituals where they express their love for the idol and shared comradery. This is called wotagei (Lin, n.d.):

The basics of wotagei include dances and cheers that place emphasis on the participants in tandem with the idol performances. Wotagei engenders itself into an amateur art form, a public expression of ritualized otaku devotion towards idols. The form shares similarities to religious and folk dance customs, including the use of costumes, central figures of worship, and synchronous chanting.

Some researchers link these performances with rituals found in Shinto where both have purification elements and expressions of joy or appreciation. Some wotagei will mimic the dance choreography of the idols. This further builds a sense of group-identity and of belonging. Fans will also create their own products in order to promote and support their favorite idols. This can take the form of art, swag, comics, and other expressions with some linking to their wotagei practice.

Because idols are every-people at the start, they offer inspiration that fans too can achieve their potential in some way. Perhaps in becoming idols themselves. Many girls join idol fan communities, and many girls audition in the hopes of becoming an idol within their favorite idol group. There are also female communities surrounding all-boy idol groups, and the female communities experience all the same benefits as male fans experience.

While I’ve focused on the fan-idol relationship and touched on the relationships among the fans themselves, idols also benefit each other. Idols have shared experiences in a difficult industry where they support and encourage each other. There is competition among idols too. There’s always ugliness, but there’s a lot less zero-sum game than you’d think. Idol groups succeed as a group, with standout artists being supported by their co-idols and with standout artists’ popularity pulling in even more fans.

In many ways, historical idol culture was the herald for today’s internet culture. People now follow their favorite streamers online just as people follow idols. Digital communication has allowed two-way communication between idols and fans along with co-creation. Fans create all sort of fan works for the idols and their community. All of this connects people, reducing depression, anxiety, and other mental health risks. Idol culture, when it works well, encourages both fans and idols to pursue their potential. Together.

References

Lin, J. A Study of Transnational Idol Otaku: Playful expressions of Japanese creative culture.

Liu, Y., Liu, Y., & Wen, J. (2022). Does anime, idol culture bring depression? Structural analysis and deep learning on subcultural identity and various psychological outcomes. Heliyon, 8(9), e10567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10567

Noémi Zs, Lampioné Gombás (2021) “ARASHI FOR DREAM” Idol—fan relationships in Japan. Centre for East Asian Studies

Sakidachi Lab (2025) アイドルを推す心理と応援活動を比較分析 〜「共感」のJ-POPと「憧れ」のK-POP」Comparative Analysis of the Psychology and Support Activities of Idol Fans — “Empathy” in J-POP and “Admiration” in K-POP. TeteMarche. https:// tetemarche.co.jp/column/genz-oshikatsu-02

Wenbo Huang, Jianquan Zhou, Xuanhong Yi, Xingwei Jing (2025)

Fans’ self-identity crisis and reconstruction in the context of idol disgraced: Evidence for a self-identity configuration, Acta Psychologica, Volume 257, 105122, ISSN 0001-6918, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actpsy.2025.105122.

Xu, J. (2022). “When They Quit from the Stage, I Quit from Learning”: Japanese Idol Fandom and Japanese Language Learning. In Online Submission.

Zhao, Y. Q. G.(2022). Analysis of the Social Impact of Fandom Culture in “Idol” Context. Advances in Journalism and Communication, 10, 377-386. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajc.2022.104022

Images

中島ゆたか, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

interiot, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Japanese Station, CC BY 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Komei shokatsu, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

I appreciated the tone of this article. It felt attentive to the human side of idol culture rather than treating it as an abstract system, which made it a thoughtful read.

One thing I’ve often felt, both as a reader and through personal experience, is that the idol culture most visible in media and scholarship represents only a small slice of a much wider world. Very large, nationally famous groups are certainly part of idol culture, but they’re far from the whole of it. Many idols — especially those who are also actresses, models, or performers working at a more modest scale — exist in a very different rhythm, with fan communities that are smaller, steadier, and deeply attentive.

In those spaces, the relationship between idols and supporters often feels less like “consumption” and more like accompaniment. Fans don’t just watch success from afar; they notice effort, growth, and persistence over time. It’s common to hear people talk about “supporting” or “walking together,” and that language reflects something sincere: a shared sense of continuity, encouragement, and mutual presence. The emotional exchange is quiet, realistic, and grounded, but no less meaningful for that.

Seen this way, idol culture doesn’t feel disconnected from older Japanese artistic traditions. The emphasis on practice, refinement, endurance, and being witnessed over time echoes values found in long-standing performance cultures — where artistry is not only about brilliance, but about dedication and showing up again and again, supported by those who care enough to notice.

I think that’s why many fans feel such genuine warmth toward idols, their fellow supporters, and even the staff who help sustain these worlds behind the scenes. At its best, idol culture can be a shared, humane project — one built on patience, attentiveness, and the quiet joy of supporting someone’s path as it unfolds.

The academic literature touched on what you describe, but as I dug around in the literature, I had the impression that more study needs to be done on the grassroots aspect of idol culture. I suspect the longitudinal nature of such studies limits the studies along with the difficulty of limiting all the other psychological and social variables on people’s lives. I suspect idol culture might offer a means of social therapy and connection as people become more isolated in the other realms of their lives. A therapist might be able to use the setting, similar to forest bathing, to help their patients.

So I got into K-Pop two years ago thanks to a friend and I became an addict ever since. This year, I went to 7 K-Pop concerts (7th one on Dec. 10). In the span of 4 months, I will have gone to 6 concerts. I have bought merchandise and now put idol photocards on display (this is also a phenomenon that I find fascinating). I also like dancing to K-Pop dance challenges if they are easy enough.

This year, I went all-in on K-Pop. I think K-Pop made me remember why I loved music in the first place. Maybe that’s why I’m not writing as much because I’m trying to live my life outside of a screen (combining that with mahjong).

That’s great! The community aspect of idol culture is the foundation for all the other benefits I found in the literature. Getting away from screens is something we all should do.