You likely haven’t heard of Hakuin Ekaku, but you’ve no doubt heard of his most famous question: “What is the sound of one hand clapping?” This question is a koan. Koans are a method, tracing back to Chinese Buddhist tradition, to break the logical mind so you can be more open to nirvana. While koans predate Hakuin’s life by centuries, Hakuin revived their popularity in Japanese Buddhist and philosophical thinking. Koans became Hakuin’s primary way of teaching his students.

Hakuin wrote extensively from his life experiences, so we know a fair bit about him. However, most of his ideas are embedded in songs, poems, folktales, riddles, and other writings that make his ideas hard to translate into English and to interpret. Considering Hakuin’s affinity for koans, this style of writing shouldn’t be a surprise!

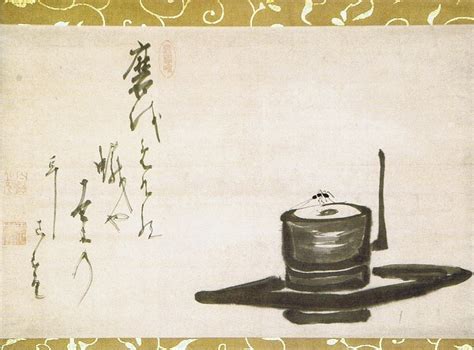

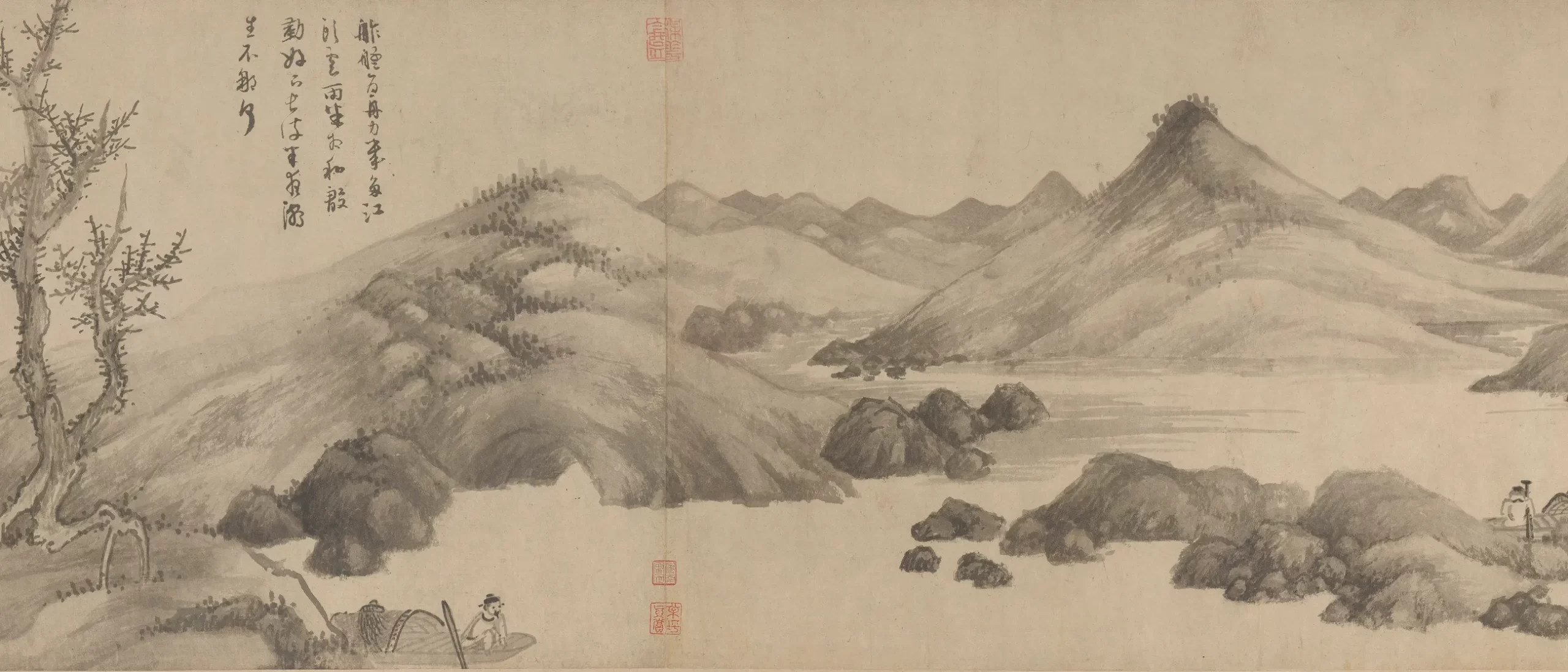

Hakuin was born in 1685. When he was young, his mother took him to a temple where he heard the priest describe the Eight Fiery Hells and the Eight Cold Hells. Later, when he went to the bathhouse with his mother, she asked the servant girl to heat the water. The sounds of the heated water terrified young Hakuin (then called Iwaya). The fear of the hells remained with him. The experience led to him becoming a monk at 13 years old. Hakuin’s autobiographical writings don’t hesitate to point out his religious doubts in the hopes his students would benefit from his own experiences. One such episode happened when he was 18 years old. He read about the historical Chinese priest Yen-t’ou being murdered by bandits. The event shattered his motivation. If such a great man could die despite his goodness, what hope did the young Hakuin have? Hakuin decided to give up his religious efforts. He began to study poetry, literature, calligraphy, and painting. He decided live life as an everyman and face the reality of the hells he feared since childhood.

However, one day, alone in the temple, he went to a hall where books had been piled up for an annual airing. After praying for guidance, he picked up a book titled “Spurring Zen Students Through the Barrier.” Inside the book he read a note in the margin:

In the past, when the priest Tzu-ming was studying at Fen-Yang, he sat through the nights without sleeping, oblivious to the bitter cold east wind of the river. Whenever the sleep demon tried to approach, he would tell himself, ‘Who are you? You’ll be worthless if you go on living, and no-one will notice if you die’, and jab himself in the thigh with a needle-sharp gimlet.

This inspired him to return to his Zen practice and the book, reportedly, remained with him the rest of his life (Clark n.d.).

Hakuin touched enlightenment at 23, but when he went to various Zen masters in an effort to have his experience recognized, none acknowledged his experience. He settled to practice with Master Shoju. Under this new teacher, Hakuin realized his meditation practice and his daily experiences of life were inconsistent. Hakuin would write:

I feel like a physician who possesses a wonderful knowledge of medicine but who has no effective means of curing an actual illness.

The experience shifted his thinking about enlightenment. He came to believe enlightenment could only be realized in everyday life. He practiced harder to align both sides of his life until at 41 years old, while reading the Lotus Sutra at night, he realized the Great Enlightenment. The experience led him to stress the need to keep training after touching enlightenment (Clark, n.d.):

Isn’t it strange that Zen practice was a great struggle for those in the past while those of today find it to be an easy, undemanding endeavour? If the easy-going attitude of today is correct, the difficulties undergone by those in the past must have been mistaken. Yet, if they were not mistaken, the easygoing attitude of today is wrong. Should we adopt the difficult path or the easy one? My position in this matter goes without saying. I choose the difficult path.

Hakuin’s Understanding of Enlightenment

Enlightenment, or nirvana, eludes a hard definition. Hakuin defines his experiences as realizing “one’s own nature.” Most of us falsely believe our nature has a self, and that this self is who we are. Hakuin would write (Giles, 2015):

There is no Buddha or Patriarch in the three periods and ten directions who has not seen into his own nature. There is no learned sage who has not seen into his own nature. This is the eternal, unchanging center of the teaching. To see your own nature is to see for yourself the True Face of the Lotus [a reference to the meaning of the Lotus Sutra]. If you do not have this desire, but think that all varieties of things are the Buddhadharma [that is, the teachings of the Buddha], you will be like a band of children that rushes aboard a boat with no captain. They do not know where they wish to go nor what the harbour of their destination is.

This nature, according to Hakuin, “is called illusory thoughts, sometimes the root of birth and death, sometimes the passions, sometimes a demon. It is one thing with many names, but if you examine it closely you will find that what it comes down to is one concept: that the self is real.” In order to break the idea that the self is real, Hakuin leaned on koans to short circuit our normal ways of thinking. His students would meditate with the koan in mind and then consult the master about their understanding of the koan. Hakuin wasn’t against other meditation techniques, but he claimed he had seen more people make progress using koans and that he struggled to make progress using other techniques. When asked about using techniques other than koans, he reportedly replied, “Which is more effective, killing a man with a sword or with a spear?” (Giles, 2015). The doubt koans intend to induce can be paralyzing, and inside that paralysis sits the realization about “one’s true nature.” Hakuin describes his own experience with this “Great Doubt”:

Night and day I did not sleep; I forgot both to eat and rest. Suddenly a great doubt manifested itself before me. It was as though I were frozen solid in the midst of an ice sheet extending tens of thousands of miles. A purity filled my breast and I could neither go forward nor retreat.

So it is with the study of the Way. If you take up one koan and investigate it unceasingly, your mind will die and your will will be destroyed. It is as though a vast, empty abyss lay before you, with no place to set your hands and feet. You face death and your bosom feels as though it were afire. Then suddenly you are one with the koan and both body and mind are cast off. This is known as the time when the hands are released over the abyss.

Hakuin equates the realization that the self is a delusion with death. When the self finally falls away, you realize the interconnection you have with everything. Hakuin would write:

when one reaches this state of realization of true reality in one’s own body, the mountains, rivers, the great earth, all phenomena, grass trees, lands, the sentient and non-sentient, all appear at the same time as the complete body of the true reality. This is the appearance of nirvana, the time of awakening to one’s own nature.

He would tell his students to hold a koan in their minds no matter what they did, from walking to sword fighting. Holding the mind in this state of logical paralysis starves the self until you realize your true nature of interdependence. Koans lack correct answers; they generated questions and tease the self which craves an answer.

Hakuin and Modern Identity

Modernity focuses on the emotive self as the basis for identity. “I feel, therefore I am.” Hakuin, and Zen in general, argues this sense of self is a delusion. Identity exists in unique Awareness, which transcends sexuality, thoughts, and other delusions the self generates. Hakuin and Zen uses negation to keep from embracing labels too closely. The Void refers to “one’s own nature.” Enlightenment, awakening, “the Great Death”, and other terms seek to avoid doctrinal labels for an individual, ineffable experience. Zen is often misunderstood as a negation of life instead of an embrace of life because of people misunderstand how Zen uses words. Hakuin would argue the modern concept of identity is a delusion we need to shed in order to become truly ourselves.

Most people have heard of Hakuin’s famous koan. While zazen has become a part of many people’s spiritual practices, koans haven’t entered popular meditation practices. Many of the traditional koans are too obscure. Here’s a koan Hakuin commented upon along with the translator’s explanation, as an example (Hoffmann, 1977):

Master Seido met the imperial messenger on the road. The imperial messenger invited Seido to dine with him. While they were dining, a donkey happened to bray. The messenger said, “Priest.” Seido raised his head, and the messenger pointed at the donkey. But Seido pointed at the messenger. The messenger was silent. Master Kido: It is the fault of a small official, me. Hakuin’s commentary: I am not very good at responding rightly to the situation. Kido’s comment and Hakuin’s substitute phrase suggest the messenger’s failure, whereas the plain saying contrasts the messenger’s overly “clever” attitude with a more natural “inviting to dine” situation.

For koans to revive in modern meditation practices, we have to do what Hakuin did in his own time: introduce new ones. Many modern Zen masters do just that, but these haven’t made it into widespread lay practice.

Hakuin’s legacy continues inside of Japanese Zen practices, but outside this circle, his legacy stands in a single statement: “Listen to the sound of one hand clapping.”

References

Clark, Judith (n.d.) Speaking Across the Generations. Middle Way. 239-251.

Giles, James (2015) Hakuin, Scepticism, and Seeing into One’s Own Nature. Asian Philosophy. 25(1), 81-98.

Hakuin. Yasenkanna. The Middle Way. 265-274.

Hoffmann, Yoel (1977) Every and Exposed: The 100 Koans of Master Kido with the Answers of Hakuin. Brookkline, Massachusetts. Autumn Press

I don’t know if you’re familiar with the Language as a Parasite Approach (“LPA”), where the brain is viewed as hosting language as a sort of parasitic software. It’s an old idea, opposing Chomsky’s view of language as emergent from native human brain function. LPA instead proposes that the brain evolved in conjunction with the benefit of being able to host the software for language, and that language is “installed” through social interaction.

In this view, language lives atop both our sensations and awareness, but functions without actual access to them. It can speak of “redness” or “love”; but it can’t actually sense or feel any of these things. Our awareness, however, can sense the voice language, and derive meaning. So conversely, language can sway or even define perceptions of “reality”. Shouting “Tiger!” can evoke the perception, regardless of whether or not a tiger exists.

The idea has lately regained some attention in debates about LLMs, whether or not they really “understand” anything, and why they “hallucinate”. (If you’re interested, Tzu-wei Hung, William Hahn, and Elan Barenholtz are serious academics working on “LPA” and some associated ideas.)

Ever notice the lack of actual descriptions for “enlightenment”, or “satori” states? Likewise, you won’t find many attempts at descriptions of certain profound hallucinatory experiences, such as with psilocybin mushrooms.

It strikes me that the whole point of Chan or Zen (or other) Buddhist meditations is to become aware of pure experience and sensation absent the definitions imposed by language. The mind stops speaking; and so the hallucinatory experience (the “tigers”) of language ceases to color perception. The result is something that becomes necessarily counter to description. And when people do attempt to describe such experiences, they sound suspiciously as a koan.

With a koan, the meditation itself is the deconstruction of language (although there is traditionally a “correct” response to one). The focus of meditation is on the very thing you’re trying to eliminate… you’re attempting to focus on language itself in order to make it irrelevant.

This falls back to one of my problems with the descriptive analysis. While it can be a functionally very powerful tool, it can also miss the point entirely when describing experiential phenomena. How does one describe “redness”?

The argument of LPA resonates with me, considering how we mistake the language labels of reality for that reality. I also find the way Zen talks around enlightenment interesting. In Christianity, many believers fail to see how Scripture talks around God in a similar way. It appears precise, just as Zen writers appear precise, but the words instead act as the event horizon around a black hole. We can detect the location of a black hole through the debris surrounding it. In a similar way, language acts as an event horizon’s matter that attempts to point toward something that exists beyond our ability to describe. But it is something we can experience. As you said, we can talk around redness, but we can’t describe redness directly to someone who is blind.